“Forging the Soul, Reflecting on History: Wu Weishan Sculpture and Documentation Exhibition” Opens

On the afternoon of December 13, the opening ceremony of the “Forging the Soul, Reflecting on History: Wu Weishan Sculpture and Documentation Exhibition” was grandly held at the Memorial Hall. Between 2005 and 2007, Wu Weishan, renowned sculptor and former director of the National Art Museum of China, was invited to design and create four sculptural groups for the Memorial Hall’s expansion project, which have since become important carriers for remembering history and expressing grief. To help visitors gain a deeper understanding of the historical significance and artistic craftsmanship behind these sculptures, the Memorial Hall specially curated this exhibition, systematically presenting the related documents and the entire creative process. The exhibition was officially opened to the public on December 14.

A Multi-Dimensional Presentation

Restoring the Creative Journey of the Group Sculptures

The exhibition is located in the audience lounge on the basement level of the Historical Materials Exhibit Hall of the Memorial Hall. This independent space serves both as a resting area for visitors after their tour and as an extended platform for historical education. As an important supplement to the Memorial Hall’s permanent exhibition, this display allows visitors to, in the intervals of experiencing the art, immerse themselves in Wu Weishan’s original intentions and creative ingenuity behind the group sculptures, enhancing the viewing experience from an artistic perspective.

Centered on restoring the creative process and interpreting the historical significance, the exhibition is divided into three parts. The first part explores the origins of the group sculptures, clearly outlining the historical context in 2005 when Wu Weishan was invited to create the works, as well as his emotional journey and reflections. The second part documents the creation of the group sculptures. Through a rich mix of multimedia videos, graphic displays, and texts, it systematically presents the conceptual thinking and internal logic behind the sculptures, including preparatory sketches, artistic concepts, creation videos, photographs, and interviews with the artist. The third part displays the sketches for the sculpture Flight. The Memorial Hall has constructed a triangular exhibition space using steel structures, harmonizing with the solemn architectural style of the building. This part showcases 66 sets of precious sketches for Flight, featuring more than 110 individual figures, and is complemented by Wu Weishan’s calligraphic works. The emotional tension conveyed through his brushwork provides a direct insight into the artist’s state of mind during creation.

Shaping History in Sculpture

Engraving the Memory of National Suffering

Traveling back to December 2005, Wu Weishan received an invitation to design and create a series of large-scale sculptures for the expansion project of the Memorial Hall. “Amid the cold winter, the north wind howled sharply. My heart felt heavy, as if time had rewound to the blood-soaked, stormy days of 1937. The fleeing, the slaughtered, the cries of despair… all lingered in my mind.”

He candidly reflected in his memoir that the expansion of the Memorial Hall was a historical necessity: “Historical facts and physical evidence form the foundation of remembrance, while sculpture can crystallize history and forge the national spirit. It can speak directly to people’s hearts, providing a basis for objective understanding and value judgment of this period of history.”

After receiving the invitation, Wu Weishan fell into deep reflection: “What should be carved? What should be sculpted? And what role should a sculptor play?” He firmly believed that only by standing at the height of human civilization and historical development, and by confronting and reflecting on the atrocities of Japanese militarism, could the works transcend mere commemoration and hatred, attaining a deeper spiritual dimension.

To ensure the sculptures were grounded in history and remained faithful to reality, Wu Weishan reviewed a vast amount of historical materials and made special visits to Nanjing Massacre survivors such as Chang Zhiqiang and Xia Shuqin, experiencing the suffering through their firsthand accounts. He repeatedly studied historical photographs, capturing emotional resonance from each real-life story depicted. “The narrative, epic-style group sculptures must not be fabricated in a simplistic, extreme, or stereotypical way.” Wu Weishan emphasized, “Only by starting from universal human nature, and considering basic human needs and the bottom line of human dignity, can the audience truly empathize.”

After countless reflections and refinements, a clear rhythm gradually took shape in Wu Weishan’s mind: “rising—descending—meandering flow—ascending—soaring.” This rhythm ultimately took form in four breathtaking sculpture groups, which were officially unveiled at the Memorial Hall on December 13, 2007.

The “Rising” corresponds to the 12.13-meter-tall Mother's Pain, whose upright form marks the starting point of suffering; the “descending, meandering flow” is embodied in the varied forms of Flight, depicting the struggles of fellow citizens through realistic figures; the “ascending” is echoed in The Cry of the Dead along the visitor route, conveying oppression and resistance through the movement of the audience; finally, the rhythm culminates in a “soaring,” with Victory Wall igniting hope for peace.

Documenting the Creation

Recording History with a Pure Heart

Upon entering the Memorial Hall, the first sculpture that catches the eye is Mother's Pain, depicting a grieving mother holding her deceased child and crying out to the sky in anguish. This sculpture stands 12.13 meters tall, symbolizing December 13, 1937, the date when the Nanjing Massacre began, and has since become an iconic landmark of the Memorial Hall.

Wu Weishan explained: “Mother's Pain depicts a mother subjected to unspeakable suffering, her powerless hands holding her afflicted child as she cries out to the heavens, humiliated yet unbowed. She represents not only countless families who endured this tragedy but also the motherland itself in its time of calamity.”

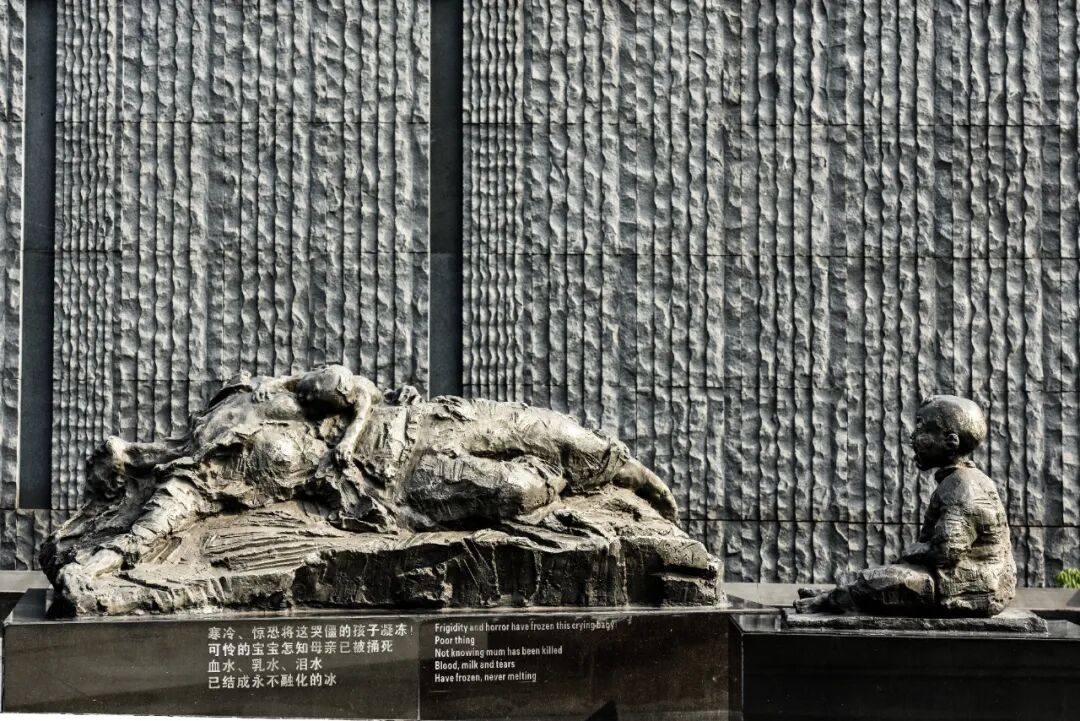

Passing by Mother's Pain, visitors are greeted by the Flight series of group sculptures. This ensemble consists of 10 groups with a total of 21 figures, each approximately life-sized. They are placed in water, creating a sense of elusive proximity to pedestrians and the surrounding architecture, as if narrating the past through an interlacing of time and space. Wu Weishan inscribed explanatory notes for each sculpture, making the pain embedded in every detail resonate deeply with viewers.

Wu Weishan said, “Among them are women, children, the elderly, intellectuals, ordinary citizens, monks, and others. What is the most heartrending is that survivor Chang Zhiqiang's mother, who gave her last drop of milk to her infant; what evokes the strongest memories is the sculpture based on a historical photo of a son supporting his 80-year-old mother while fleeing; what is the most thought-provoking is the monk who wiped the eyes of the deceased, still filled with grievance… These 21 figures, interweaving reality and imagination, form a sorrowful, dramatic curve.”

As visitors move forward, The Cry of the Dead delivers a powerful visual impact. The sculpture resembles two “mountains” split by a soldier’s sword. The left “mountain” symbolizes the wronged souls pointing to the sky in questioning, while the right depicts the scene of innocent civilians being massacred. The irregular shape conveys a sense of instability, symbolizing the power of resistance.

Wu Weishan stated, “It is both the gate of flight and the gate of death.” The split mountain shape symbolizes the shattered homeland, with the opening naturally forming a passage into the Memorial Hall. The left triangular section points skyward, representing a wronged soul crying out for justice. The right section depicts the scene of civilians being slaughtered; it rises from the ground, piercing the clouds, emitting a roar of grievance and calls for righteousness.

Upon arriving at the Memorial Hall Peace Plaza, visitors encounter a giant relief wall called the “Victory Wall.” Centered on the theme of “Victory”, its design is based on a “V”-shaped structure, measuring 140 meters in length and 8 meters in height. The relief portrays powerful narratives: “The Roaring Yellow River, Advancing Amidst Enemy Fire” and “The Surging Yangtze River, Celebrating the Victory of the Chinese People's War of Resistance.” At the junction of the “V” shape, a sculpture, a Chinese soldier blowing a victory trumpet is depicted. He stands with invaders’ helmets and broken command swords beneath his feet, blowing the trumpet of victory with high morale.

After completing the group sculptures in 2007, Wu Weishan wrote a poem and had it cast onto the sculptures: “With unspeakable sorrow, I recall those blood-soaked storms; with trembling hands, I caress the grievances of the three hundred thousand lost souls; with a heart of utmost sincerity, I carve the suffering of this tormented nation. I pray, and I hope, for the awakening of this ancient nation—the rise of its spirit!!!”

Forging the Soul, Reflecting on History

Passing Down Historical Memory Through Generations

These four groups of sculptures have long transcended the realm of art itself, becoming profound vessels in which the artist’s personal emotions merge with the collective memory of a nation and the shared emotional heritage of humanity. Today, as visitors enter the Memorial Hall, they first pass through the Statues Square, where many pause in contemplation, deeply moved by the powerful emotions conveyed through the sculptures. Many young people, through the tangible figures and lifelike scenes embodied in the sculptures, gain a direct and profound understanding of the weight of history, allowing that historical memory to be passed down from generation to generation.

One of the sculptures in Flight recreates the lived experience of survivor Chang Zhiqiang: at the age of 9, he witnessed his father, elder sister, and younger brother brutally killed by Japanese troops. His mother, gravely wounded in the chest, struggled to feed the last drop of milk to her two-year-old son before closing her eyes forever. In his later years, Chang Zhiqiang often came to stand quietly before the sculpture, lingering in silence as if “conversing” with his departed loved ones.

On December 13, 2007, the renowned physicist Chen Ning Yang, then 85 years old, visited the Memorial Hall to attend a mourning ceremony. While viewing the group of sculptures, he was deeply moved and said, “It reminds me of the scenes during the Japanese bombing. The sound of those bombs falling is something that no one who lived through it could ever forget!”

From the completion of the sculptures in 2007 to the opening of the current documentary exhibition, Wu Weishan’s works have enabled more people to understand the suffering of the 300,000 victims, allowing the commitment to remembering history and cherishing peace to take root deeply in people’s hearts.

Wu Weishan donated his calligraphic works to the Memorial Hall