International Archives Day The Discovery of The Diary of Cheng Ruifang

One day in December 2001, as winter was coming, researcher Guo Biqiang was sitting at the table and working as usual at the Second Historical Archives of China (SHAC) in Nanjing. Suddenly, the door opened and several people walked in, with a yellowing document in their hands. “Mr Guo, we found this while sorting out scattered files from Ginling College. It might have to do with the Nanjing Massacre.”

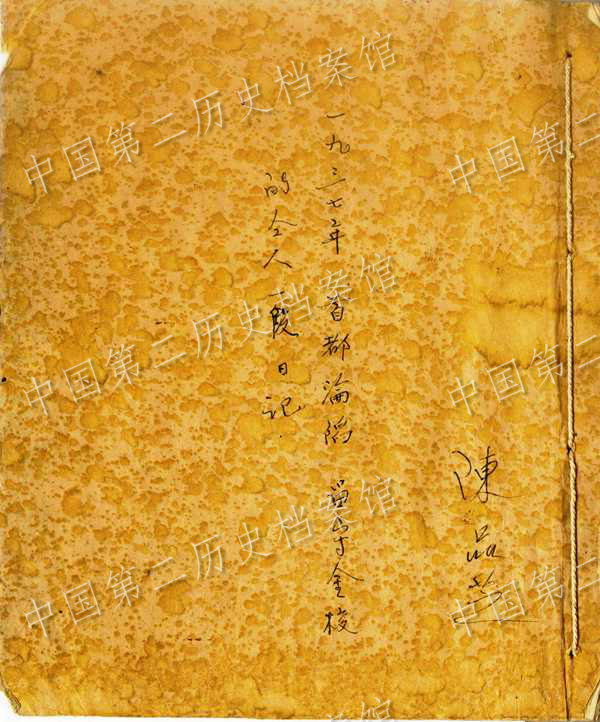

Guo took the document and started looking through it. It was a diary. Guo saw a sentence on the front cover: “In 1937, the capital was captured. A diary kept by someone who stayed behind in Ginling College.” The diary contains about 30,000 words. Guo read the diary in one sitting. While reading it, he seemed to be able to feel the helplessness, anger and sorrow of the person who wrote the diary, sometimes pounding the table to express his anger, and sometimes lapsing into silence.

Who wrote the diary? What was recorded in it? And what was special about the diary? On the International Archives Day, the Memorial Hall invited Guo to the Zijin Cao Peace Lecture to tell the story behind the diary.

What’s special about a diary?

Starting from early 2001, staff members at the SHAC began sorting out thousands of scattered archives of Ginling College (renamed Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences in 1930). In the face of old files covered with dust, no one would have thought that a treasure was hidden among them.

Guo said the yellowing diary was so ordinary that it didn’t get their attention at first. It was one year later that the staff members finally discovered it as they organized the files carefully.

“It’s a diary, a diary written by a Chinese to record the Nanjing Massacre. The diary wrote about what happened from December 8, 1937 to March 1, 1938.”

On December 13

“So deplorable. Who knows what would happen tomorrow!”

On December 14

“More people fled to the college today, all from the Safety Zone. The Japanese soldiers broke into their houses during the daytime and robbed them of money or raped women. On the street, many people were stabbed to death. The situation was so terrible in the Safety Zone, not to mention what was happening outside it. No one dared to go out. Most of the people killed were young men.”

On December 17

“It’s already midnight, but I can’t sleep. I’m sitting here and writing the diary. Today, I know what a conquered people means.”

On December 18

“So horrible. These Japanese soldiers are savage and do all kinds of bad things. They kill or rape people, whether old or young, at their will.”

On December 22

“The Japanese soldiers don’t allow people to go out and look at the corpses on the streets. Corpses are piling up on some streets. They are not even treating Chinese as people.”

On December 29

“The Japanese soldiers are clearing the streets, burying or burning the corpses. The streets are filled with corpses.”

……

Every word and sentence was frightening. Guo read the diary with sorrow, anger and helplessness. “The diary offered a detailed account of what was really happening during the Nanjing Massacre. I guess the owner of the diary must have witnessed the atrocities of Japanese troops when they burned the houses, killed and raped people, and plundered things from them.”

Who is the owner of the diary?

Who is the owner of the diary? Is it possible to find her and confirm everything? Guo let his eyes settle upon the name on the cover: Chen Pinzhi.

But after investigation, the staff members soon found that the diary was not written by Chen Pinzhi. Chen Pinzhi was a biology professor at Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences, but she led some teachers and students to Wuhan before Japanese troops captured Nanjing.

Then Guo did a rough analysis based on the contents of the diary. “The diary was included in the archives of Ginling College, so I believe the real owner should be an educated staff member living in school.”

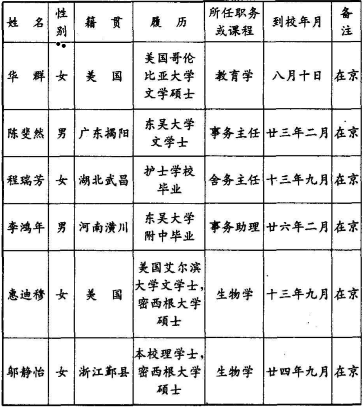

To find the real owner, the staff members searched the Record of Teachers and Administrative Staff at Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences. It listed six staff members who stayed in Nanjing. Guo guessed one of them must be the owner.

“Of them, two were American, including Minnie Vautrin (whose Chinese name is Hua Qun); Chen Feiran and Li Hongnian were male in their 30s; Wu Jingyi was female but she was only about 30 years old then. In her diary, the writer mentioned her grandson participated in the services team at Ginling College. He should be more than 10 years old. So only Cheng Ruifang, who was in her 60s, met this condition. And she was educated and relatively safe,” Guo said.

In summer 2003, Guo and his colleagues went to the handwriting identification center of the Jiangsu Public Security Bureau. They submitted the copies of the personal information forms filed in by Cheng and Chen Pinzhi, as well as the copies of the cover and inside pages of the diary for handwriting identification.

“It was confirmed that the words on the inside pages were written by Cheng while the words on the cover were written by Chen Pinzhi. So we are sure Cheng wrote the diary and Chen Pinzhi kept the diary for her.”

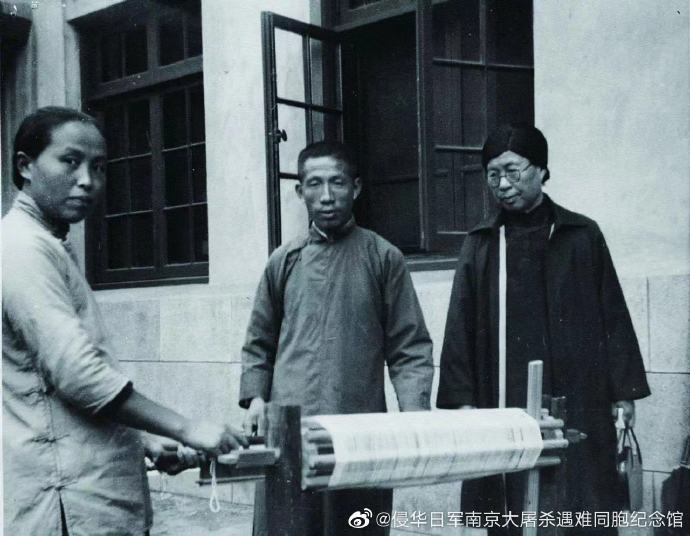

Cheng Ruifang (1875-1969) was born in Wuchang, Hubei. After the refugee camp was set up at Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences, Cheng, who was serving as dormitory supervisor, assisted Minnie Vautrin in managing the refugee camp.

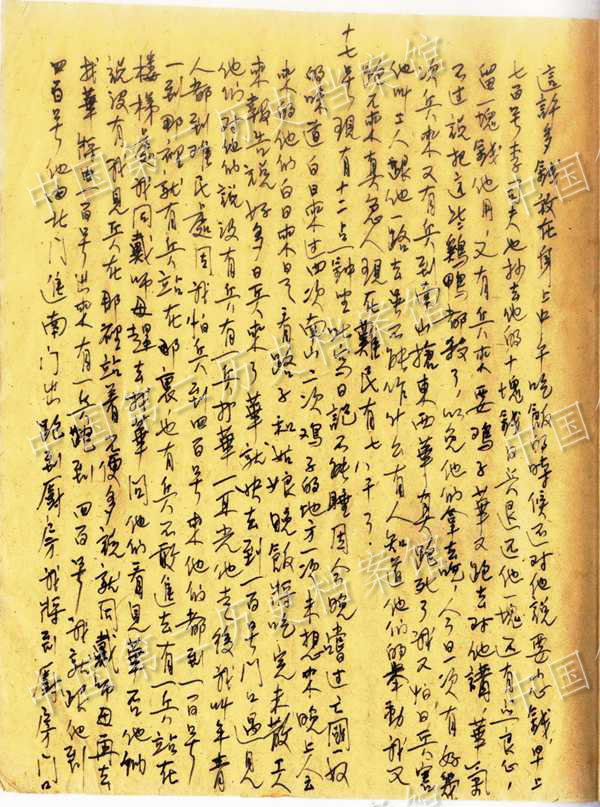

Through the handwriting of Cheng in the diary, Guo caught a glimpse into her mind while she wrote the diary. “The color of the ink went from dark to light, and then became dark again. I guess she didn’t dip her pen into the ink unless it ran out of ink. She must have so many feelings to express that she couldn’t stop. I also noticed that she wrote many things that happened on the same day in different times. I guess there must be some kind of turbulence that distracted her from continuing the diary. We can imagine how harsh the environment was then.”

Cheng Ruifang (R) helps a woman taking refuge at Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences spin a yarn to making a living

How did the diary get kept?

Cheng wrote her last diary on March 1, 1938. What happened to the diary after that?

Given the situation in Nanjing at that time, Guo said, once the Japanese invaders discovered Cheng’s diary, they would definitely destroy it and Cheng’s life would be at stake. In 1938, Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences was moved to Huaxiba in Chengdu, Sichuan. To keep the diary safe, Cheng might have asked her international friend to carry the diary to Chengdu.

“After Japan surrendered, the school was relocated back to Nanjing. I guess the diary was taken back to Nanjing at that time. Later, along with other archives of the school, the diary was sealed up and archived by the SHAC in the 1960s.”

An excerpt from The Diary of Cheng Ruifang

Where did Cheng go?

“In 1946, 71-year-old Cheng wrote an English testimony to the the International Military Tribunal for the Far East as part of the evidence revealing the Japanese invasion of China. In her testimony, Cheng described the crimes of Japanese troops on campus, including raping, robbing and slaughtering Chinese people,” Guo said.

In 1952, 77-year-old Cheng returned to her hometown in Wuhan, Hubei. In 1964, 90-year-old Cheng was invited to visit the former site of Ginling College. In 1969, Cheng passed away in Wuhan at the age of 94.

What’s the value of the diary?

“So far we have discovered some diaries written by the witnesses to the Nanjing Massacre. Among them, John Rabe and Minnie Vautrin were foreigners. The Diary of Cheng Ruifang was the first diary found ever that was written by a Chinese who experienced the Nanjing Massacre. The diary provides a truthful historical resource that is more reliable and accurate than other historical materials.”

A group photo of Cheng Ruifang (front row, fifth from left) and some other staff members at the refugee camp at Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences

Guo said the diary of Cheng complements the diaries of the two international friends, representing an integral and important part of the irrefutable evidence regarding the Nanjing Massacre.

“For example, both Cheng and Minnie Vautrin mentioned how the Japanese soldiers beat up Chen Feiran, a manager of the refugee camp. In her diary for December 17, 1937, Vautrin wrote, ‘Mr Chen spoke up and wanted to help me, but he was hit hard by the Japanese soldiers.’ Cheng wrote about the same thing, ‘Chen Feiran was afraid that Vautrin doesn’t understand, so he called himself coolie. The Japanese soldiers slapped his face, kicked him, dragged him to the opposite, and then ordered him to kneel down.’ If he didn’t speak up, he wouldn’t be beaten.”

They also recorded the celebration of the birth of Chen Feiran’s son. “On February 12, 1938, Vautrin wrote, “We ate oranges and popcorn brought from Shanghai to celebrate the birth of Chen Feiran’s son.’ Cheng also wrote, ‘Today there’s a boat and also letters from Shanghai. I’m happy. And there’s also delicious food.’”

A group photo of Cheng Ruifang (R), Minnie Vautrin and Chen Feiran (L)

These are just two examples of facts in their diaries that echo each other, Guo stressed, adding that they form a complete and irrefutable chain of evidence.

What role did the diary play?

“When China submitted the documents of the Nanjing Massacre to the UNESCO for inclusion on its Memory of the World Register, the diaries of Cheng played a significant role. It was the first archive sample,” Guo said.

Guo took part in the whole process of applying for listing the documents related to the Nanjing Massacre including The Diary of Cheng Ruifang in the Memory of the World Register. Despite the difficulties and pressure, he never thought about giving up. “For me, this is not only my job, but also an obligation I think I should assume. I hope these documents can be known, understood and remembered by more people.”

“As an educated mature woman, Cheng offered a vivid and detailed account that allowed readers to experience the history and thus have a clearer, specific and thorough understanding of the darkest days of Nanjing. This diary deserves to be remembered by more people.”