84 Years Ago Today, She Took Her Own Life. She Was Also a Victim of the Nanjing Massacre

On May 14, 1941, American Minnie Vautrin turned on the gas in her apartment kitchen, ending her life at the age of 55. This "living bodhisattva," who had protected tens of thousands of Chinese women and children during the Nanjing Massacre by the Japanese invaders, ultimately became a victim of the war atrocities.

This morning, in front of the statue of Minnie Vautrin at the "Nanjing Massacre Exhibit," visitors spontaneously laid chrysanthemums, her favorite flowers in life.

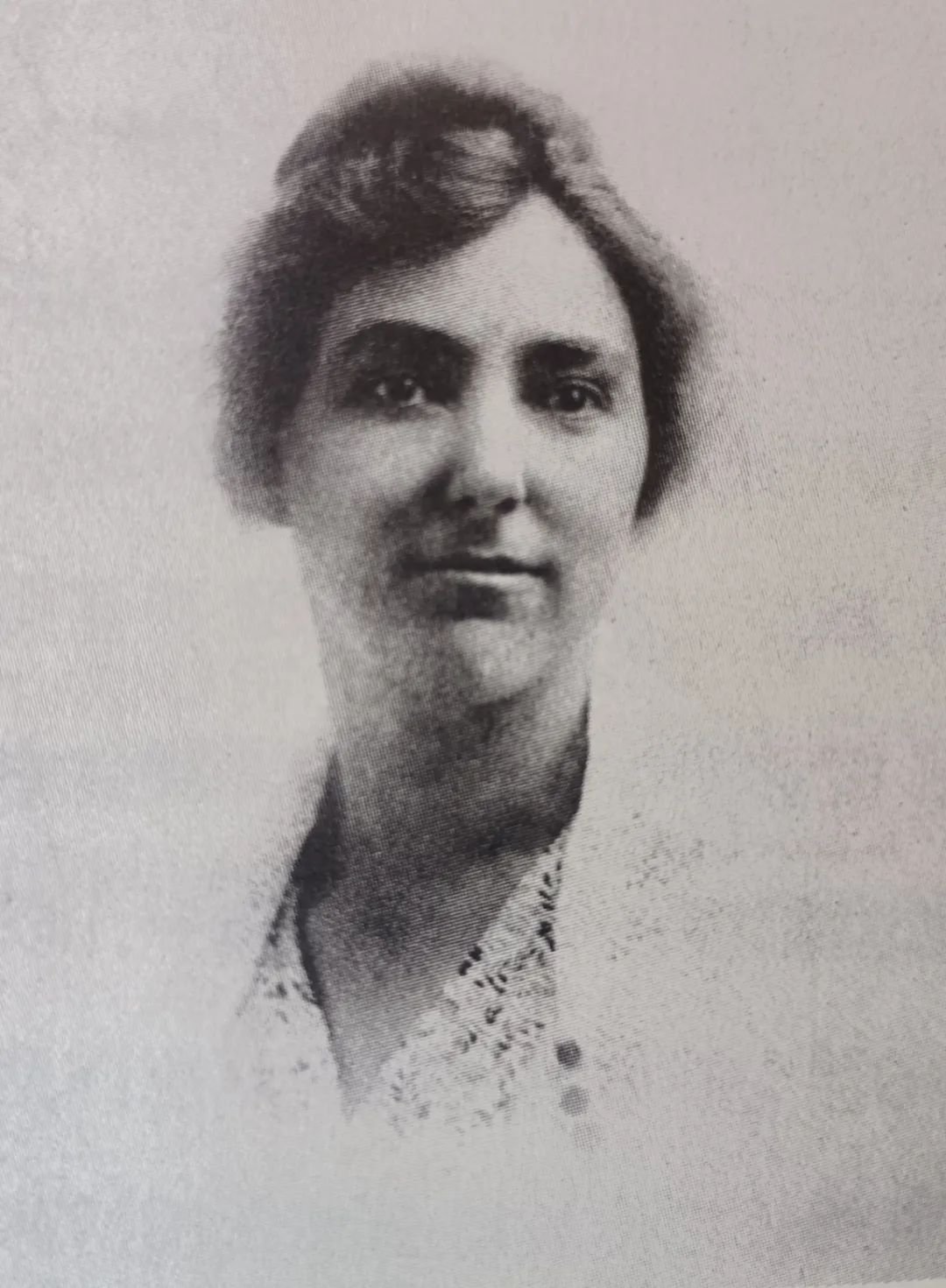

Minnie Vautrin (1886-1941)

Born into Poverty

Minnie Vautrin was born on September 27, 1886, in Illinois, USA. Her father ran a blacksmith shop. When Minnie was six years old, her mother passed away due to illness. At the age of 12, after her father remarried, she was sent to live with neighbors. Even in the coldest days of winter, she had to take care of the livestock. Despite these hardships, Minnie managed to complete her high school education through a combination of work and study.

High school graduation photo of Minnie Vautrin in 1903 (from Hu Hualing's Jinling Everlasting: The Biography of Minnie Vautrin)

In 1903, after graduating from high school, Minnie Vautrin chose to study education at the University of Illinois out of respect for the teaching profession. Sometimes, she had to return to her small town to teach in order to earn enough money for her tuition. In 1907, Vautrin graduated from university and was hired to teach at a secondary school. However, she felt that her knowledge was far from sufficient and resigned to pursue further studies in education at the University of Illinois. According to records preserved by the university, among the more than 500 graduates in 1912, Vautrin ranked second in her academic performance.

Minnie Vautrin in 1912

After that, Minnie Vautrin chose to come to China and served as the principal of Sanyu Girls' Middle School in Hefei, where she worked and lived for six years.

Standing Firm in Times of Crisis

In the fall of 1918, Minnie Vautrin was granted a leave of absence to return to the United States. After visiting her family, she immediately went to Columbia University for further studies and obtained a master’s degree in education from the university. As her vacation was about to end, Ginling College (renamed "Ginling Women's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences" in 1930, now the Suiyuan Campus of Nanjing Normal University) needed a suitable candidate to temporarily take over the administration since its president, Mrs. De Puy, was about to return to the United States for a vacation. Due to her remarkable achievements at Sanyu Girls' Middle School in Hefei, Minnie Vautrin was considered the most appropriate candidate. Through the efforts of many parties, Minnie Vautrin arrived in Nanjing in October 1919 and was appointed Dean of Studies at Ginling College, also serving as the acting president for a year and a half. From then on, she began a relationship with Nanjing that would last for over 20 years.

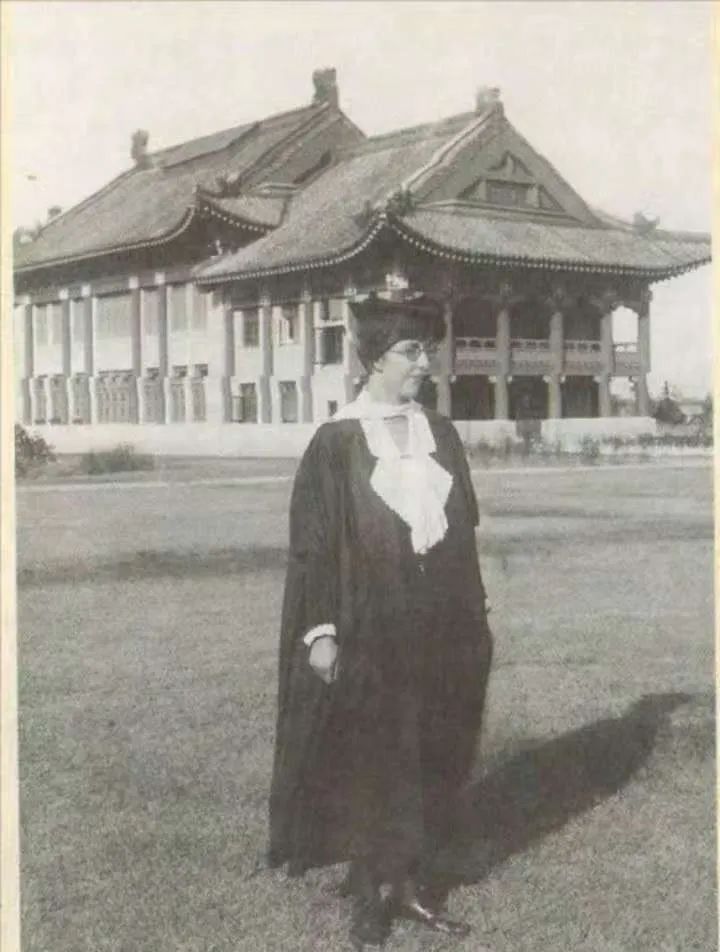

Minnie Vautrin at Ginling College

On August 15, 1937, when Japanese aircraft first bombed Nanjing, Minnie Vautrin, who was then the Dean of Studies at Ginling Women's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, immediately organized the faculty and students to take shelter in the basement.

Japanese military planes bombing Nanjing (from China Front Photo Album, Volume 29, Issue 21)

On the evening of August 22, American professor Lossing Buck at Jinling University called Minnie Vautrin, informing her that the U.S. Embassy hoped all American women and men without special reasons should prepare to evacuate Nanjing. Vautrin insisted that she had a critical mission and could not leave immediately. On the evening of August 27, the U.S. Embassy in China sent Vautrin a strongly worded letter, notifying her that the embassy's women would evacuate Nanjing the next day. Vautrin firmly refused, stating,

"Just as men should not abandon a ship in danger, women should not abandon their children."

On the morning of September 20, an official from the U.S. Embassy in China, Paxton, came to Ginling Women's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences to inform Vautrin of the impending bombing of Nanjing by the Japanese military and to persuade her to temporarily leave Nanjing for a few days to avoid any accidents. However, Vautrin still decided not to leave. A few hours later, she wrote a letter to Paxton, clearly expressing her determination not to evacuate Nanjing. In the letter, she wrote:

"I feel that it would be a tragedy if all the embassies in the city lowered their flags and withdrew their personnel because it would mean that Japan could ruthlessly and unscrupulously bomb Nanjing without even a formal declaration of war, and I hope the Japanese air force will not have that satisfaction."

Minnie Vautrin also stated that she was voluntarily taking the risk to stay behind and did not want to put the U.S. government or Ginling Women's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences in a difficult position, no matter what happened. She would take full responsibility herself. On November 12, the Japanese military occupied Shanghai and then advanced towards Nanjing in several directions.

Promoting the Establishment of the "Safety Zone"

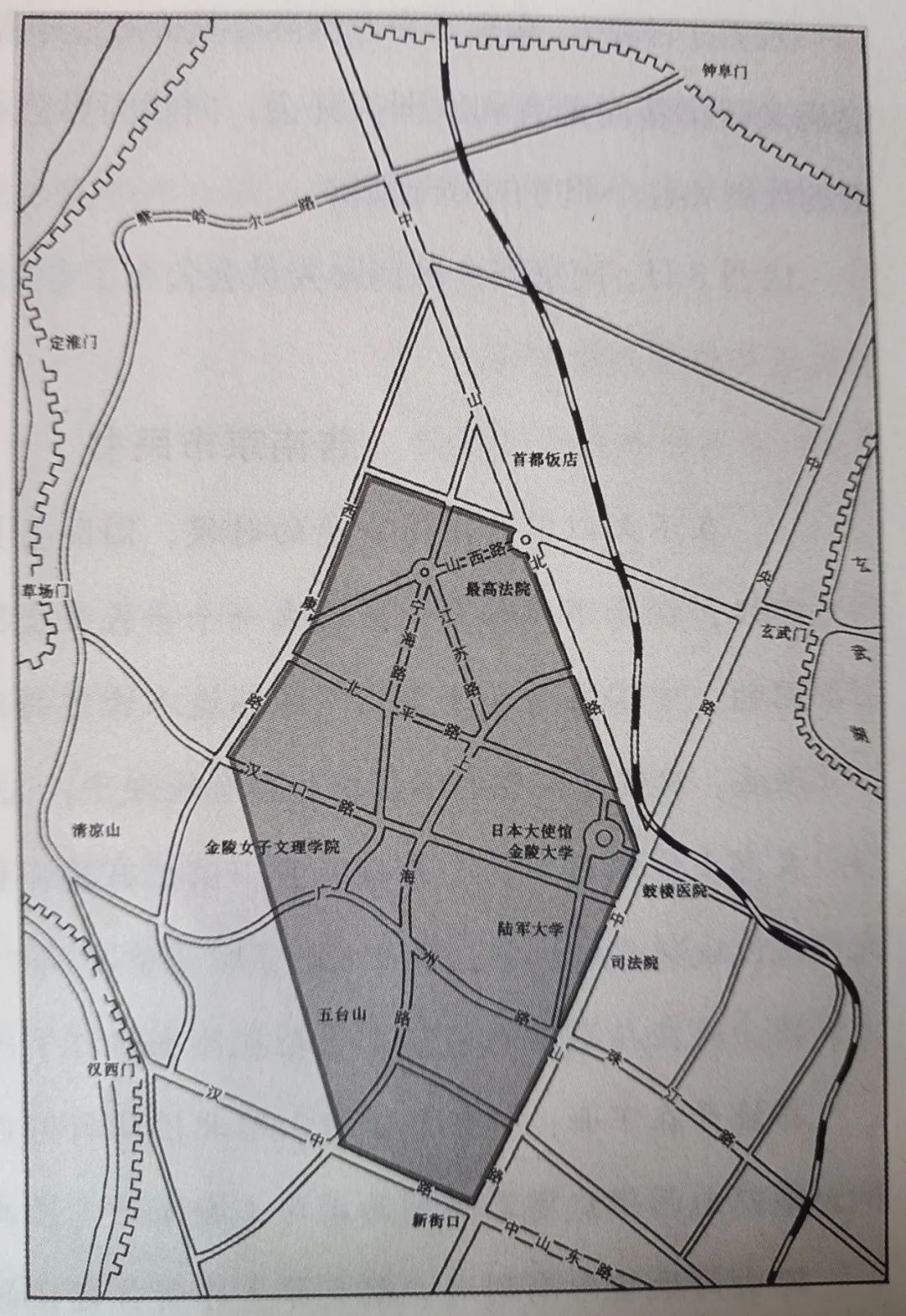

On November 17, Minnie Vautrin wrote to Peck, an official at the U.S. Embassy in China, suggesting the establishment of a safety zone in Nanjing to protect refugees. It is evident from the letter that she was inspired by the refugee zone in South Shanghai. After receiving the letter, Peck immediately reported the matter to the U.S. Ambassador to China, Johnson. Johnson agreed with the idea and conveyed it to both the Chinese and Japanese sides on their behalf.To Vautrin's delight, on November 24, the International Committee for the Safety Zone had demarcated the boundaries of the safety zone, which included Ginling Women's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. She and her colleagues began to vacate spaces in preparation for receiving refugees.

Map of the Nanjing Safety Zone

On the evening of December 8, Ginling Women's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences welcomed its first group of female refugees. Overwhelmed by exhaustion, Minnie Vautrin wrote in her diary, "Tonight, I look 60 and feel 80."

Refugees carrying bedding and other items entering Ginling Women's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (Yale Divinity School Library)

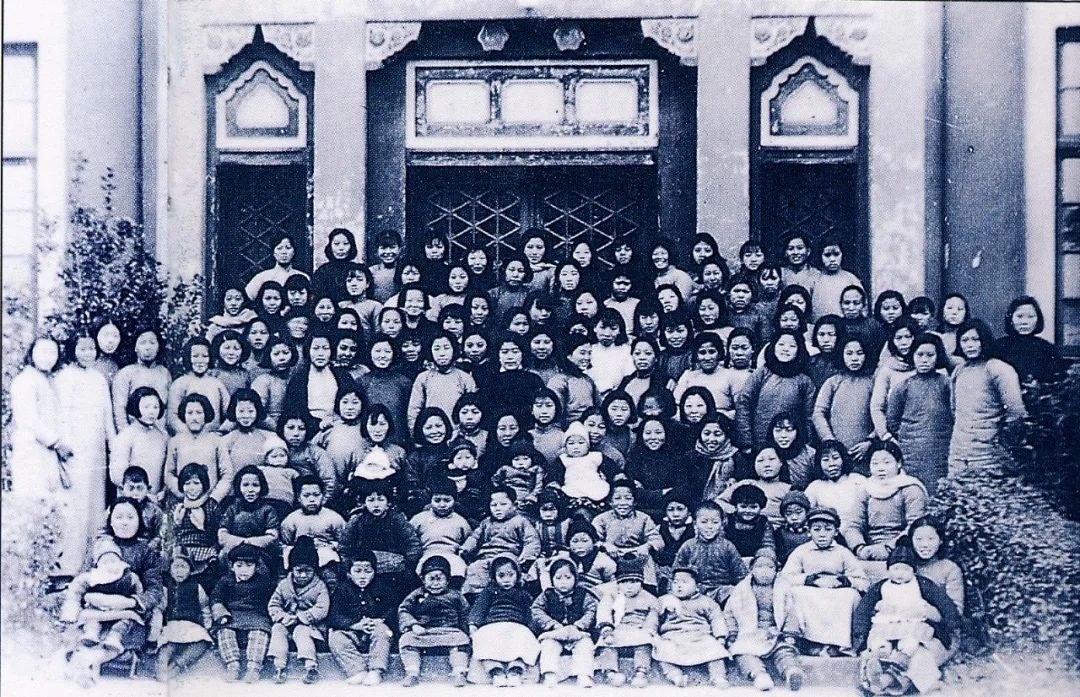

Staff and workers of the refugee camp at Ginling Women's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, with Minnie Vautrin sitting fourth from the left in the front row and Cheng Ruifang fifth from the left

Protector Amidst the Atrocities

On December 13, 1937, the day Nanjing fell, three groups of Japanese soldiers stormed into the campus demanding supplies. Starting from December 14, Minnie Vautrin almost guarded the school's main gate around the clock to prevent Japanese soldiers from entering and to maintain order at the entrance, allowing those who met the criteria to take refuge on campus. However, the situation continued to deteriorate.

Vautrin's diary entry on December 19 recorded a harrowing experience:

"In Room 538 upstairs, I saw one man standing at the door while another was raping a girl. My appearance and the letter from the Japanese Embassy in my hand caused them to flee in a panic."

On December 26, her assistant, Cheng Ruifang, wrote in her diary:

"Hua (Minnie Vautrin's Chinese name 'Hua Qun') is not feeling well today, probably due to exhaustion... These refugees call her the Goddess of Mercy, the savior from suffering."

During the Nanjing Massacre, thanks to Minnie Vautrin's courageous protection, the refugee camp at Ginling Women's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences was relatively safer compared to other refugee camps.

On February 4, 1938, the Japanese military authorities forcibly demanded the dissolution of the refugee camp. However, not only did Vautrin refuse to close the camp, but she also took the risk of accepting many young women from other refugee camps and rural areas. Even after the official dissolution of the refugee camp in May, Vautrin continued to shelter over 800 people under the pretext of summer school sessions.

A group photo of some women and children at the closing of the refugee camp at Ginling College

The Chinese government highly appraised Minnie Vautrin's heroic deeds. On July 31, 1938, the Chinese government secretly awarded her the "Blue, White, and Red Tricolor Ribbon with Jade Medal" in recognition of her contributions.

The Irreparable Wound

The continuous atrocities inflicted severe psychological trauma on Minnie Vautrin. In the spring of 1940, she was diagnosed with depression and often blamed herself for "those she couldn't save." She wrote in her diary:

"In my imagination, there always linger the shadows of suffering soldiers... It probably isn't right for us to enjoy life while they are enduring such terrible pain."

When Minnie Vautrin left China and returned to the United States on May 14, 1940, she was already frequently having suicidal thoughts. After receiving convulsive therapy at a psychiatric sanatorium in Iowa, she briefly improved, but ultimately, she took her own life on May 14, 1941—the anniversary of her departure from Nanjing.

During her illness, Vautrin remained deeply concerned about Ginling Women's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and hoped to return to China once she had recovered. In her letters to friends, she always wrote, "For many years, I have deeply loved Ginling College and have tried my best to help her." She also often said to those around her, "If I had a second life, I would still wish to serve the Chinese people."

"Minnie Vautrin Is Also a War Casualty"

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions declared in the obituary: "Like a soldier who fell on the battlefield, Minnie Vautrin was also a casualty of war." Vautrin's suicide was primarily caused by severe depression, one of the significant triggers of which was the trauma inflicted by the Japanese military's atrocities in Nanjing. Japanese scholar Kano Jiro pointed out: "It was the Japanese military's attack and occupation of Nanjing that caused Minnie Vautrin's mental breakdown and subsequent suicide... She was one of the victims of the Japanese invasion of China."On May 18, in the suburbs of Shepherd, Michigan, USA, a solemn and dignified funeral was jointly held for Vautrin by the Missionary Union and the American Board of Trustees of Ginling Women's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. On the front of her rectangular tombstone, an architectural section of Jinling Women's College is engraved. Within the gable roof, four Chinese characters are inscribed vertically in strong and elegant Clerical script: "Eternal Jinling."

That afternoon, in China, the faculty and students of Ginling Women's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences held a memorial ceremony simultaneously. President Wu Yifang summarized Minnie Vautrin's contributions to Jinling Women's College and the Chinese people: "She was one of the victims of the war, and she dedicated her life to China."

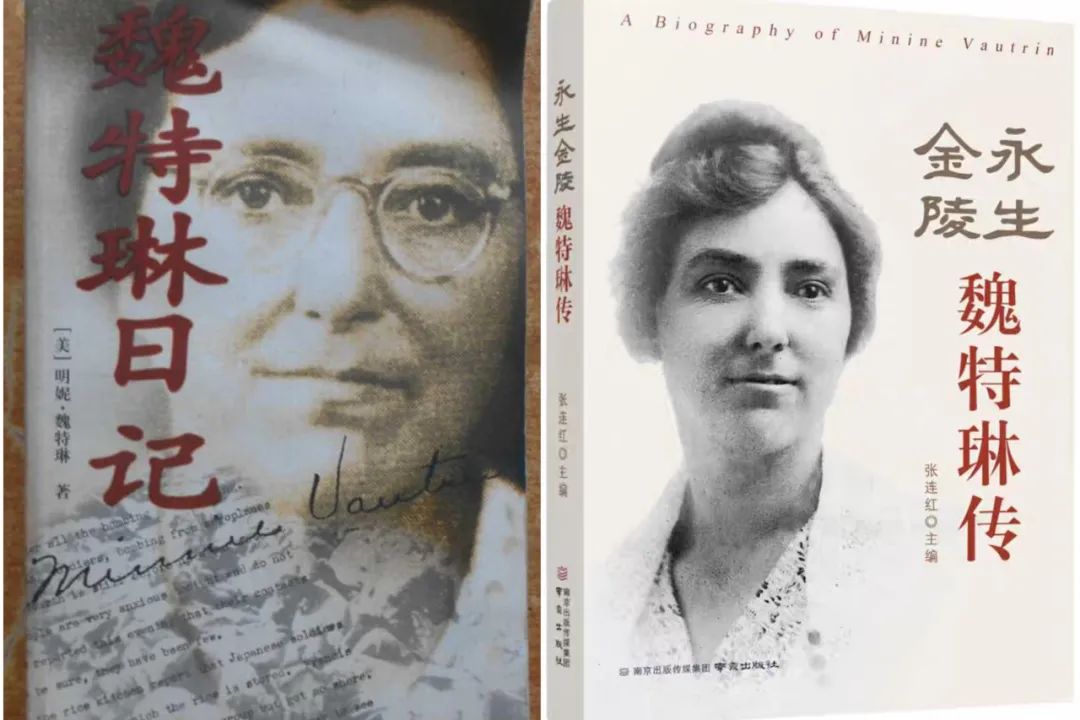

Nanjing Will Never Forget

In 1998, the Nanjing Massacre Research Center was established on the campus where Minnie Vautrin had served for 21 years. Scholars immediately identified Vautrin and the refugee camp at Ginling Women's College as important research topics. Ms. Smalley from the Special Collections Room of the Divinity Library at Yale University provided the photocopy of the original manuscript of The Diaries of Minnie Vautrin to the research center. Scholars divided the work of translating The Diaries of Minnie Vautrin and wrote The Biography of Minnie Vautrin, which was published successively in 2000. China Central Television, Jiangsu Television, and other media outlets subsequently produced several television documentaries about Minnie Vautrin. Her story of saving women refugees during the Nanjing Massacre has been widely disseminated.

The research on the Nanjing Massacre by the Nanjing Massacre Research Center of Nanjing Normal University has never been interrupted. On December 13, 2024, the eleventh National Memorial Day for the Victims of the Nanjing Massacre, the book Eternal Jinling: The Biography of Minnie Vautrin was officially published. This book, which spans over 300,000 words, cites a substantial number of historical materials and integrates more than 20 years of research findings from the Nanjing Massacre Research Center at Nanjing Normal University and the broader academic community. Zhang Lianhong, the editor-in-chief of the book, Vice President of Nanjing Normal University, and Director of the Nanjing Massacre Research Center, introduced that "the editorial committee analyzed the impact of war trauma on individuals by using a large amount of medical theoretical data, combined with The Diary of Minnie Vautrin and her medical reports after returning to the United States." He said, "Minnie Vautrin was also a victim of the Nanjing Massacre."

To this day, in front of Minnie Vautrin's statue at the "Nanjing Massacre Exhibit" in the Memorial Hall, people spontaneously lay white chrysanthemums, her favorite flowers in life, to honor this brave and great woman. Similarly, at the bronze statue of Vautrin on the Suiyuan Campus of Nanjing Normal University, flowers are often placed in tribute.

Minnie Vautrin, the heroine of the Nanjing Massacre, will forever be remembered in Jinling!