American Friends We Should Never Forget

Before and after Nanjing fell in 1937, some foreigners stayed in the city. They helped save refugees, and at the same time recorded and spread the truth behind the Nanjing Massacre to the world. Of those westerns, more than 20 were Americans, including John Magee and Minnie Vautrin.

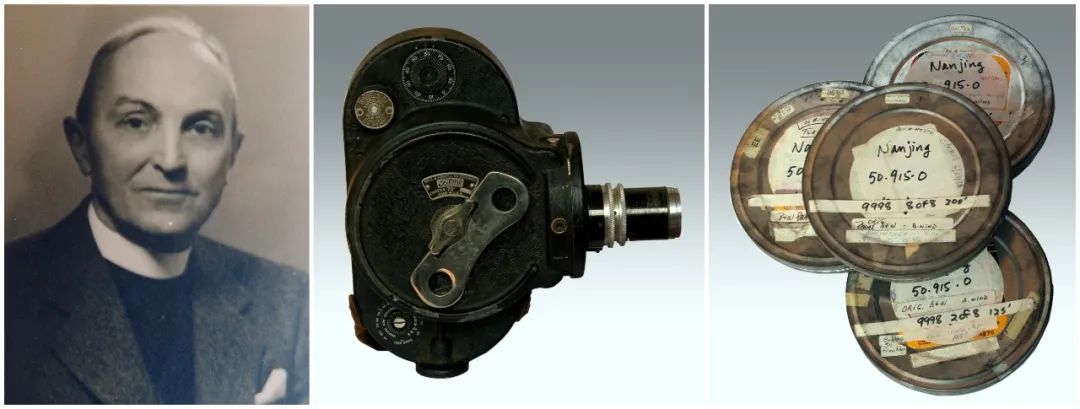

American Filming and Spreading the Truth

After the Japanese army seized Nanjing, American priest John Magee remained in the city and secretly recorded evidence of Japanese war crimes with his Bell and Howell 16mm movie camera, including scenes in the city after the murders and severely injured locals being treated at the Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, leaving what is known as the only visual evidence so far that revealed the atrocities committed by Japanese troops during the massacre. In an introduction to his film, Magee indicatedhow careful he must be so as not to let the Japanese see him doing it.The camera used by Magee and film negatives of the video became an important part of the Documents of the Nanjing Massacre inscribed on the Memory of the World Register by the International Advisory Committee of UNESCO’s Memory of the World Program in 2015.

John Magee, his camera, and film negatives

After World War II, Magee appeared in court as a witness as the International Military Tribunal for the Far East was convened to try Japanese war criminals in Tokyo. Later, some survivors who appeared in his film, including Xia Shuqin, Li Xiuying, and Wu Changde, became historical witnesses to the Nanjing Massacre.

In his film, for example, Magee recorded the miserable scene after the Japanese soldiers killed seven of the nine members in Xia’s family.

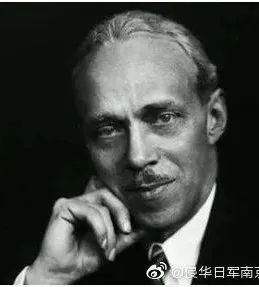

After seizing Nanjing, the Japanese army imposed lockdowns and checks, making it difficult for Magee to bring his film out and expose the truth about what happened to the world at once. Another American George Fitch, general secretary of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone, learned that and decided to help. Born in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, in January 1883, Fitch developed a Chinese name (Fei Wusheng) during his time in the country. In 1937, he stayed in Nanjing to help establish the Nanking Safety Zone.

George Fitch

In January 1938, Fitch found an opportunity to leave Nanjing and got on a Japanese military train bound for Shanghai. By sewing the reels into the lining of his coat, Fitch wisely escaped the investigation from the Japanese army and successfully transported the film out of Nanjing. Upon arrival, Fitch immediately handed the film over to Eastman Kodak Company in Shanghai and asked them to develop the film and make some copies. In March 1938, Fitch returned to the US and started doing his part to expose the truth about the Nanjing Massacre. He toured the eastern and western parts of the country to give speeches and show the movies shot by Magee to the audience.

Americans Offering a Helping Hand to Refugees in the Refugee Camps

After Nanjing fell into the hands of the Japanese army, some Chinese and foreign teachers, fearless in the face of danger, stayed on campus. Of the 25 refugee camps inside the Nanking Safety Zone, five were set up at the University of Nanking, known in Chinese as Jinling University, which accommodated about 50,000 refugees in total.

Refugees at Jingling University

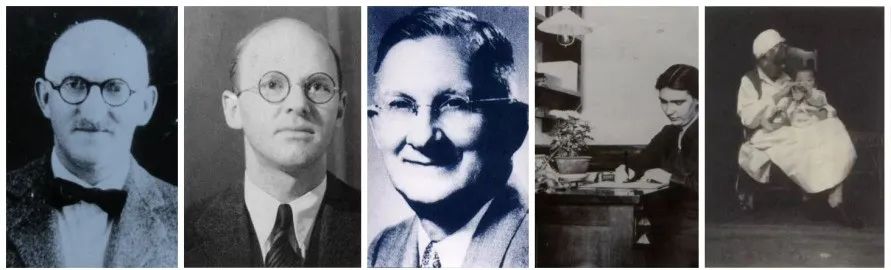

Professors at Jinling University, including Miner Searle Bates and Lewis Strong Casey Smythe, not only protected the refugees during the daytime. At night, they remained on duty to prevent the Japanese soldiers from robbing refugees of their property and raping women. When seeing many refugees suffered from beriberi caused by malnutrition because they could only have porridge for a long time, they managed to transport broad beans from Shanghai to help them get vitamins. They also thought of ways to transport milk powder and cod liver oil from Shanghai to help improve nutrition for the children there.

Miner Searle Bates

To make the refugees’ life colorful, the refugee camps of Jinling University held a training session in the North Building New Year’s Day in 1938. More than 30 teachers, including American Mary Twynam and some Chinese teachers, gave lessons to them.

The courses, designed to equip the refugees with moral grounding, intellectual ability, physical vigor, aesthetic sensibility, and work skills, covered a wide variety of subjects, including elementary/advanced math, English, and Chinese, physical education for females and males, hymn, music, labor, and Bible studies. The refugees could sign up for courses depending on their ability and interest to enrich their life, just like students during peacetime.

Of course, keeping the classes running was not an easy thing. While defending against the Japanese soldiers, Charles Henry Riggs (Chinese name Lin Chali), a professor of agricultural engineering at Jinling University, was beaten up by them. Nonetheless, the teachers and students never gave up. They used their actions to let the Japanese invaders know that they might be able to occupy their home temporarily, but they would never be able to break their will.

Charles Henry Riggs

Apart from Jinling University, Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences (named Ginling College before 1930; today’s Nanjing Normal University Suiyuan Campus) was designated as a refugee camp for women and children. The refugee camp was headed by American Minnie Vautrin (whose Chinese name is Hua Qun). Vautrin came to China from the US in 1912 and taught at Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences for a long time.

A group photo of Minnie Vautrin (fourth from left, front row) and some other staff members of the Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences refugee camp

After invading Nanjing on December 13, the Japanese army began cruelly slaughtering Chinese people in what was known as the Nanjing Massacre that shocked China and the whole world. Enveloped in an atmosphere of terror, women and children came to Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences in swarms. Every day, Japanese soldiers took some refugees away from the college, raped women, and robbed refugees of their money, breaking in through the front and side doors, or climbing over the walls, or even climbing over the lower fences at night (in search of women). Vautrin patrolled the campus throughout the daytime and assigned foreign males to stay on guard in turns at night, in case Japanese soldiers should appear and arrest women. That irritated some Japanese soldiers who threatened her with a bayonet full of blood and even slapped her face. But Vautrin didn’t yield and still did her best to protect tens of thousands of Chinese women and children on campus from being harmed by the Japanese soldiers.

A group photo of some women and children taking shelter in Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences

American Doctors and Nurses Saving and Treating Refugees

The Drum Tower Hospital, also known as the University of Nanking Hospital, was the earliest and largest church hospital in Nanjing.

On the eve of the fall of Nanjing, over 20 medical workers, including five American doctors and nurses and their Chinese colleagues, risked their lives and stayed to save patients severely injured by the Japanese army day and night. The five Americans were administrator James H. McCallum, doctors C. S. Trimmer and Robert O. Wilson, and nurses Iva Hynds and Grace Bauer.

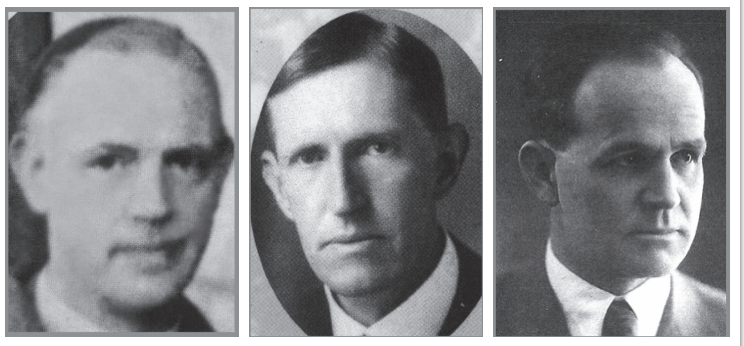

From left to right: C. S. Trimmer, Robert O. Wilson, James H. McCallum, Grace Bauer, Iva Hynds

Robert O. Wilson was the only surgeon in Nanjing then. Although an American, Wilson was born and grew up in Nanjing. He often used the first person pronoun to talk with Chinese people. As the only surgeon, Wilson faced heavy tasks of performing surgeries. On December 14 alone, he completed 11 surgeries; and by December 18, up to 150 patients were waiting to be treated by him. To make himself have the energy to do surgeries, he even injected hormones into his body. Even if that had consumed much of his energy for the day, he still worked outside at night to prevent the Japanese army from carrying out violent acts. Both the intense physical work and huge psychological pressure eventually ruined his health, and in 1940, he had to return to the US to receive treatment.

Robert O. Wilson was examining a patient

While medical workers were saving lives desperately, hospital administrator James H. McCallum tried his best to ensure the supply of daily necessities for the staff members and patients, in spite of the great risks. McCallum was responsible for transporting grain and patients for the hospital, an extremely arduous and dangerous task. This was because after the Japanese army seized Nanjing, Chinese workers must be accompanied by a foreigner to deliver food such as Chinese cabbages and rice successfully to the hospital. McCallum also helped pick up babies and patients. “Have a new job. Been delivering babies. O yes, Trim and Wilson DELIVER them, but I take them home ...” McCallum wrote in the letter to his family for January 5, 1938.

Iva Hynds and Grace Bauer, who had been working at the Drum Tower Hospital, also choose to stay. McCallum mentioned their work in his letter to his family for December 29, 1937. “A foreigner must be on duty 24 hours here at the hospital in order to deal with the Japanese visitors. ... Have had fifteen or twenty babies within the last week; six on Christmas Day. It is easy to find Miss Hynds; she is always in the nursery mothering the whole crowd of babies.”

Richard Brady was another surgeon of the Drum Tower Hospital. In December 1937, Richard sent his wife and daughter to Hong Kong and then prepared to return back to Nanjing. But he was stopped by the Japanese and didn’t go back to the hospital until February 1938. After that, he assisted in Robert O. Wilson Wilson in saving patients. Today, the descendants of Richard still maintain a friendship with Nanjing.

Despite the dangers, every worker in the hospital, whether Chinese people or foreigners, went all out to complete their work. “Two American doctors, Frank Wilson and C. S. Trimmer, and two American nurses, Grace Bauer and Iva Hynds, labored day and night with only a few Chinese helpers to care for the nearly 200 patients in their charge,” said Frank Tillman Durdin, a correspondent for The New York Times, in an article on December 22, 1937.

American Reporters Covering the Nanjing Massacre

Before the Japanese troops seized Nanjing, five Western reporters also gave up the last chance to evacuate and chose to remain in the city without hesitation as war correspondents. Four of them were Americans. They were Frank Tillman Durdin of The New York Times, Archibald Trojan Steele of The Chicago Daily News, Arthur von Briesen Menken of The Paramount Newsreel, and Charles Yates McDaniel of The Associated Press. They reported on what they experienced and saw in the city and broke the frontline news to the outside world.

Archibald Trojan Steele of The Chicago Daily News had been reporting from the frontlines during the Battle of Nanking. When the Japanese army invaded the city on December 13, 1937, Steele and four other Western reporters still chose to stay, recording the dark moments they witnessed.

Archibald Trojan Steele

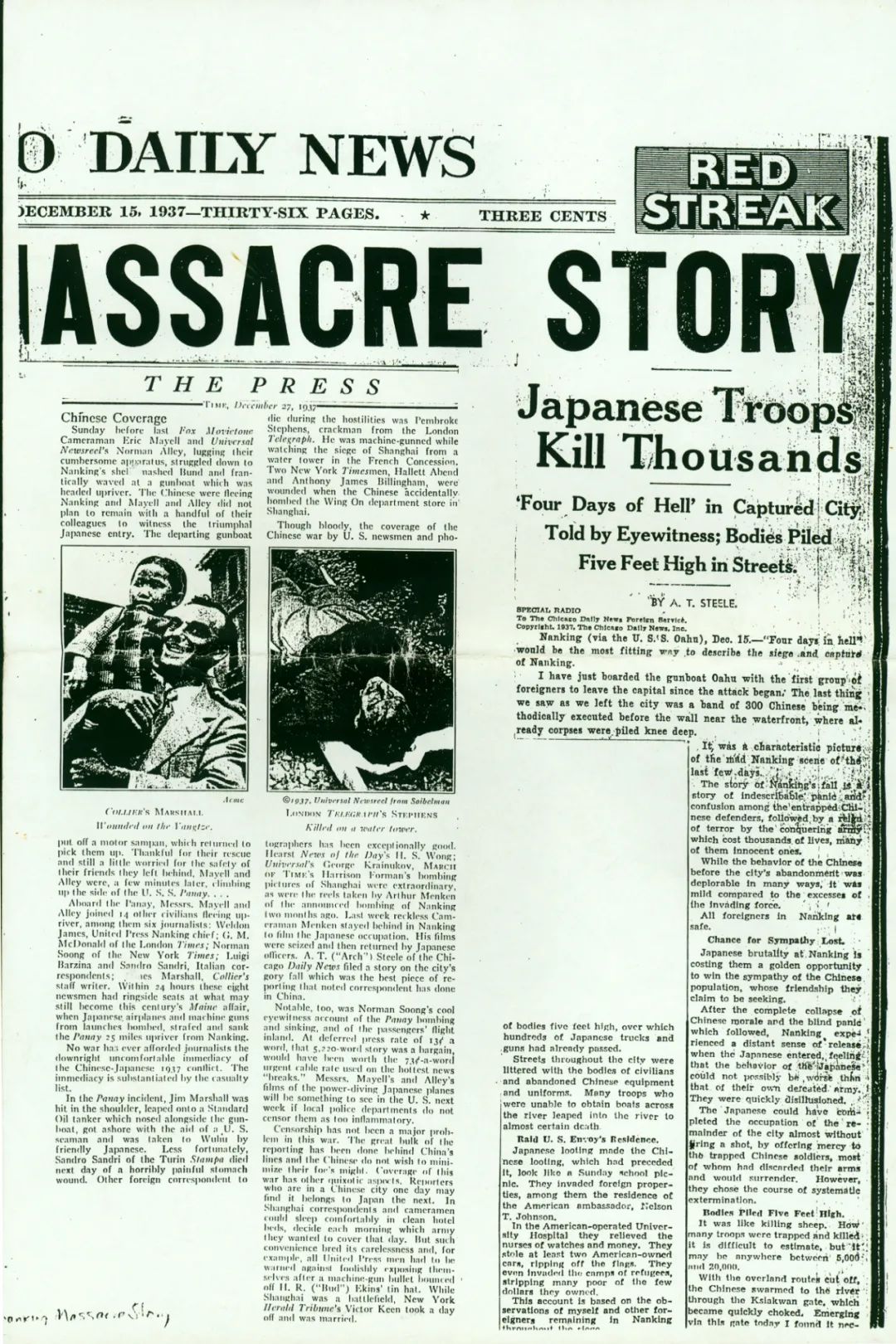

On December 15, after negotiating with the Japanese military, Steele and some other Western reporters were allowed to board US Navy gunboat USS Oahu bound for Shanghai. As soon as he got on the ship, Steele went to the telegraph room to send out his latest dispatch. That was the article printed on the front page of The Chicago Daily News on December 15, 1937: Japanese Troops Kill Thousands, with the subtitle “Four Days of Hell” in Captured City Told by Eyewitnesses; Bodies Piled Five Feet High in Streets. According to historical materials found so far, this report was the earliest printed account of the Nanjing Massacre after it took place.

The report published on The Chicago Daily News on December 15, 1937. This was the world’s first report about the atrocities committed by the Japanese army in Nanjing after the massacre happened

Frank Tillman Durdin of The New York Times was the first journalist who used the term that meant a massacre. On December 18, 1937, Durdin cabled a dispatch via radio on a US gunboat, with the banners “Butchery Marked Capture of Nanking – All Captives Slain. Civilians Also Killed as the Japanese Spread Terror in Nanking”. The article was printed on the front page of The New York Times.

American reporter Frank Tillman Durdin

“Most of the Chinese soldiers who had been interned in the safety zone were shot en masse. The city was combed in a systematic house-to-house search for men having knapsack marks on their shoulders or other signs of having been soldiers. They were herded together and executed. Many were killed where they were found, including men innocent of any army connection and many wounded soldiers and civilians. I witnessed three mass executions of prisoners within a few hours Wednesday,” Durdin wrote in his report.

The front page of The New York Times on December 18, 1937

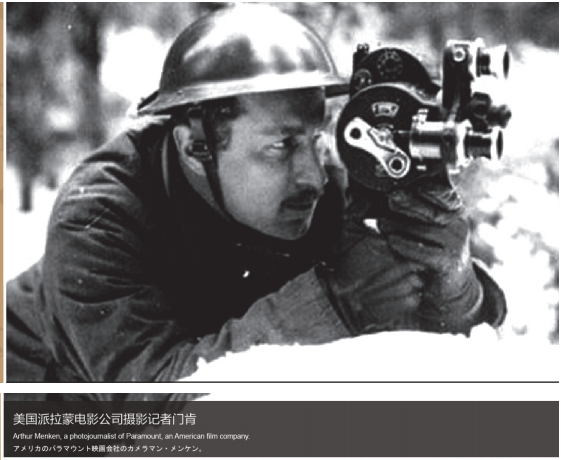

Arthur von Briesen Menken was a press photographer for The Paramount Newsreel. Anyone in the city would witness not only a bloody battle, but also killing, looting, raping and other crimes against humanity committed by the Japanese army in and near Nanjing. Menken witnessed the destruction and looting of the American Embassy by the Japanese soldiers. Together with Durdin, Menken drove out five Japanese soldiers who broke into the kitchen of the American Embassy.

At the same time, Menken anxiously hoped that he could lay bare to the public the atrocities committed by the Japanese army as soon as possible. On December 15, 1937, Menken, together with Steele and Durdin, boarded the US patrol gunboat Oahu berthed in the Yangtze River to leave for Shanghai. The next day, he finally sent his telegraphic dispatch to The Associated Press via the Oahu radio facility.

On December 17 US time, The Chicago Daily Tribune published the article sent by Menken from China, titled “Witness Tells Nanking Horror As Chinese Flee”, on Page 4. “All Chinese males found with any signs of having served in the army were herded together and executed,”Menken indicated in his dispatch. He also described the horror Nanjing endured in his eyes. “The once-proud capital of ancient China was strewn today with the corpses of its soldier defenders and civilians killed in the bombing, shelling and fierce fighting to which the city was subjected.”

The report on the Nanjing Massacre by Arthur von Briesen Menken published on The Chicago Daily Tribune on December 17, 1937

Charles Yates McDaniel of The Associated Press was the last foreign correspondent to evacuate, leaving Nanjing on December 16, 1937. “I could do nothing. My last remembrance of Nanking: Dead Chinese, dead Chinese, dead Chinese,”McDaniel wrote in his dispatch (publishedon The Chicago Daily Tribune on December 18, 1937).

The Chicago Daily Tribune issue on December 18, 1937

We Shall Not Forget

Other Americans who remained in Nanjing during the massacre included:

Ernest H. Forster, an American Episcopal Church priest and chairman of the Nanjing Branch of the International Red Cross after Magee.

Wilson Plumer Mills, a Northern Presbyterian Mission minister and vice chairman of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone.

Hubert Lafayette Sone, a missionary at Nanjing Theological Seminary and associate food commissioner of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone.

From left to right: Ernest H. Forster, Wilson Plumer Mills, Hubert Lafayette Sone

Gratefulness is a Chinese virtue, as expressed by an old Chinese saying — “A drop of water in need shall be returned with a burst of spring in deed.” Over the past more than 80 years, the Chinese people have never forgotten the humanitarian spirit and brave and righteous acts of those Americans. And the descendants of those Americans living across the vast Pacific Ocean have stayed together with Nanjing over these years.

Chris Magee, grandson of John Magee, has visited Nanjing, the city his grandfather once lived, for many times. Following the footsteps of his grandfather in Nanjing, the professional photographer has filmed what Nanjing looks like today. A photo exhibition held by the Memorial Hall in 2018 combined his photos with those of his grandfather in a dialogue across time and space. Chris said he really wanted to take a walk with his grandfather in today’s Nanjing, a city of peace.

Megan Brady is the great granddaughter of Richard Brady. Megan created a song Mercy inspired by the experiences of Richard. At the candlelight vigil on the national memorial ceremony for the victims of Nanjing Massacre held on December 13, 2019, Megan sang the song with her ethereal voice and moved a lot of people. The song was sung for peace, she said.

The son and daughters of Dr. Wilson come to Nanjing nearly every year during the national memorial ceremony. They have also recorded an oral history with the Memorial Hall.

...

This friendship spread across time and space originated in the light of humanitarianism in darkness. Over the past 86 years, that friendship has grown even stronger with shared aspirations for peace!

Upper: Chris Magee Lower left: Elizabeth Wilson Hissing Lower right: Megan Brady