Nanjing Massacre in the Eyes of Germans

The year 2022 marked the 50th anniversary of the establishment of China-Germany diplomatic relations. Go back 85 years in history, a group of Germans fostered deep bonds with Chinese people.

They observed, recounted and analyzed the Nanjing Massacre as a third party. They not only tried their best to save Chinese refugees, but also recorded the suffering of Chinese civilians and unarmed soldiers in a detailed and accurate manner. Their records provided evidence of the crimes of the Japanese army in Nanjing, including slaughter, rape, looting, and arson.

They were John Rabe, Karl Guenther, George Rosen, Paul Scharffenberg, Christian Jakob Kröger, Eduard Sperling, and Oskar Paul Trautmann. Today, let’s revisit their stories.

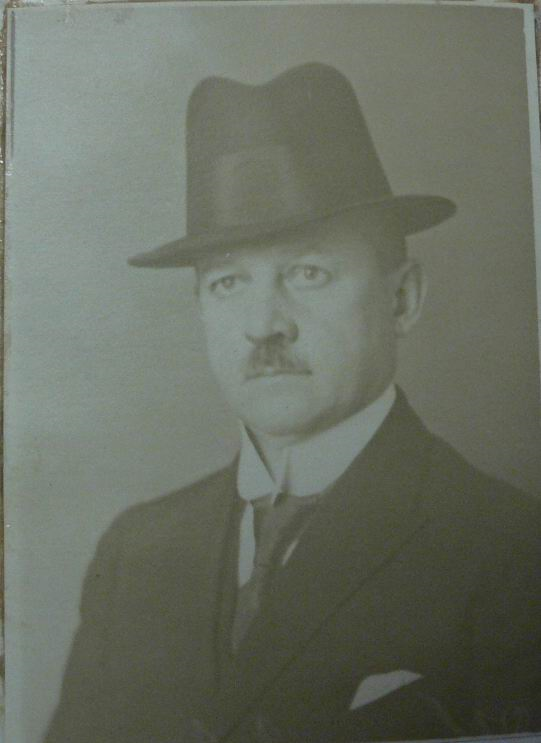

Rabe, director of Siemens Nanjing Office and chairman of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone

Of the German we have known so far, Rabe produced the most detailed accounts of the Nanjing Massacre. Almost every type of crimes committed by the Japanese army could be found in The Diaries of John Rabe.

The Nanking Safety Zone led by Rabe saved the lives of more than 250,000 Chinese refugees, including over 600 refugees sheltered in his residence at No. 1 Xiaofenqiao on Guangzhou Road. He was hailed as “a living Buddha” by the refugees.

However, Rabe suffered from physical and mental exhaustion as he witnessed endless miseries and finally decided to leave Nanjing. Before he left, thousands of women surrounded his car, crying for losing his protection.

On May 2, 1938, the 17th day Rabe returned to Germany, he projected US priest John Magee’s visual video about the Nanjing Massacre. He also delivered four speeches about the massacre.

During a speech delivered at the Koerber Foundation in Berlin, Germany in March 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping praised Rabe and said “we in China cherish the memory of Mr. Rabe as a man who demonstrated great compassion for life and love of peace.”

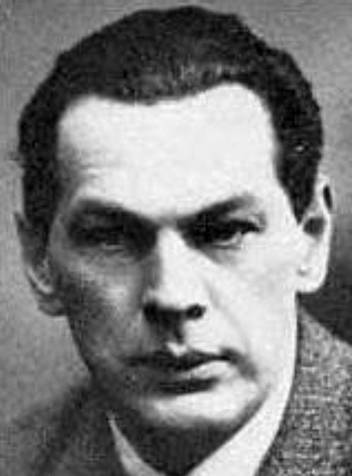

Guenther, German engineer

In 1937, Jiangnan Cement Factory, Asia’s largest cement factory, was completed in the northeastern suburb of Nanjing and started operation. That coincided with the Japanese invasion of Nanjing. Unwilling to let it fall into the hands of the Japanese army, the Board of Directors of the factory urgently hired German engineer Dr Guenther from Tangshan in Hebei to prevent occupation by the Japanese.

After the city was captured, Guenther, along with a Danish colleague Bernhard Arp Sindberg, stood together with Chinese people in the eastern suburb of Nanjing. The cement plant sheltered more than 20,000 refugees from nearby areas, many of whom fled from Qixia Temple because the refugee camps there were constantly harassed and attacked by the Japanese soldiers.

Besides, Guenther stopped the Japanese army from forcibly demolishing facilities in the cement factory and worked to safeguard its security to prepare for the resumption of production.

After the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, Guenther continued to work at the factory as an engineer and didn’t return to Germany until the factory produced cement after the People’s Republic of China was founded.

Rosen, secretary of German Embassy in China Nanjing Office

Before the Japanese troops reached the city of Nanjing, Rosen was invited to board a British ship near Nanjing, which offered him a chance to keep himself away from the atrocities taking place in the city. However, Rosen and some British officials were refused when they wanted to return to the city. “The real reason was that Japan does not want us to see the deplorable scene of rape, burning, killing, and looting that the completely unbridled Japanese army has unleashed on the civilians of Nanjing.”

On January 9, 1938, the German embassy’s office in Nanjing reopened. In the first official report to the German Federal Foreign Office, Rosen mentioned that the Japanese troops began clearing away corpses immediately after some diplomats said they would return to Nanjing. But such a slaughter that had no parallel in modern history of the world was so large in scale and long in duration that they could not completely destroy the evidence of their crimes. “This arson, organized by the Japanese military, is still going on to this day — a good month after the Japanese occupied the city — as is the abduction and rape of women and girls. In this respect, the Japanese army has erected a monument to its own shameful conduct,” Rosen said.

After seizing Nanjing, the Japanese frankly told some “secrets” to westerners in Nanjing. Rosen, who knew those “secrets”, wrote them into the report to the German Federal Foreign Office.

Rosen recorded the process of the Nanjing Massacre with the same rigor as Rabe. For example, he once inspected the place which occurred in the video of John Magee.

Paul Scharffenberg, office administrator of German Embassy in China Nanjing Office

Scharffenberg did no less than Rosen to expose the atrocities of the Japanese army.

On February 15, 1938, after persistent requests against Japanese military restrictions, Scharffenberg was finally allowed to enter the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum area. He was shocked by what he saw along the way. “We got as far as the swimming pool. The lovely willows along the road near the pagoda have all been chopped down and almost all the villas have been burned down. We could not walk in the area because there were still too many corpses, blackened and partially eaten by dogs.” And, the city of Nanjing littered with bodies faced serious public health problems. “The weather is very changeable at present. When it’s as warm as it is today, you can’t go out on the streets for the stench of corpses.”

Lots of evidence of the massacre could be found even in the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum area where access was allowed. This obviously didn’t satisfy the Japanese troops which wanted to leave a good impression on foreigners.

On March 4, 1938, Scharffenberg reported to German Ambassador to China Trautmann: “They are now hard at work removing bodies from the center of the city. The Red Swastika Society has been given permission to bury the 30,000 bodies in Hsiakwan. They manage 600 a day. The bodies are wrapped in lime and straw mats, with only the legs hanging out, then driven back into the city and buried in mass graves also filled with lime. It’s said that circa 10,000 have been dealt with.”

Christian Jakob Kröger, treasurer of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone

On December 28, 1937, at the climax of the massacre, Kröger drove to Qixia Mountain to investigate the atrocities of the Japanese army, finding that Japanese soldiers “indiscriminately killed all farmers including women and children with guns in the field”, but he admitted he “had to courage to be a hero”.

Kröger’s car was looted by Japanese soldiers, and his servant was threatened with bayonet to open the door and hand over everything to them. More seriously, three corpses were put at his door for weeks. He saw and recorded the crimes committed by the Japanese soldiers, including robbery, murder, and rape.

Japanese right-wing forces often spread rumors that it was Chinese soldiers who burned Nanjing to the ground. In fact, Kröger witnessed their act according to his testimony in late January 1938:

“Since December 20, 1937, the Japanese began to systematically burn down the city and thus far have been so successful that about one third of the city has been burned down, especially the South City, the main business district, as well as individual commercial buildings and residential districts near our house. The burning has diminished somewhat now, that is, at present they are burning down only a few houses that were previously overlooked or otherwise missed. Before burning, all the houses were plundered completely by organized squads with trucks.”

Eduard Sperling, an employee at Shanghai Insurance Company and inspector-general of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone

As the inspector-general of the Safety Zone, Sperling inspected one place after another to chase away the Japanese soldiers and protect Chinese refugees. His colleagues in the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone called him “a fortress of the committee”.

Sperling was in charge of 650 Chinese police officers in the safety zone. He said he had “esteem and respect for the Chinese race, who, as I have often seen, is willing to endure their suffering and sorrow without complaint or grumbling.”

In such an unbearable situation, Sperling was one of the few foreigners who always kept his spirits up. “In well over 80 cases, I was called by Chinese civilians to drive off Japanese soldiers who had forced their way into houses inside the Safety Zone and were violating women and young girls in the most dreadful manner. I did so without any serious difficulties,” he said proudly.

But the Japanese army would not stop their atrocities because the hard work of Sperling. Even in March 1938, violence hard to imagine was still continuing. Facing the situation, Sperling tried his best to save Chinese civilians.

Oskar Paul Trautmann, German ambassador to China

Most reports made by Germans were forwarded by Trautmann. In addition to spreading appalling news to the German government and the world, he also recorded the Japanese army’s crimes including looting and massacre during the Nanjing Massacre.

At the same time, Trautmann noticed the effects of the Nanjing Massacre on the Chinese people. “China has awoken. The Japanese army has caused hitherto undiscovered patriotism long buried in the hearts of the Chinese people to sprout. All attempts by the Japanese to establish an independent government produce only an image that they can persist only at the tip of Japanese bayonets.”

This observation was echoed by an American observer, who wrote the following in an article, “The defiance in the faces of these Chinese, led away on that last death march, is the greatest proof I could offer that China is at last a nation as we ‘patriotic’ westerners understand the word.”

Of course, as the ambassador, Trautmann focused on analyzing the far-reaching impacts of China-Japan conflicts on international relations in the Far East and how Germany should cope with them.

These Germans risked their lives to save Chinese refugees in different ways. We will never forget their humanitarian spirit and brave and righteous acts.