“What does the Nanjing Massacre Have to do with Me” Episode Five Wang Huo: First Reported the Nanjing Massacre to Uphold Fairness and Justice

He ran through the flames of war, broke through the enemy’s blockade, and survived the artillery attack; he was among the earliest journalists in China to report the Nanjing Massacre after the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, and was the first journalist to interview Li Xiuying, a survivor of the Nanjing Massacre; he also wrote the War and People trilogy set during the period of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, which was his magnum opus…

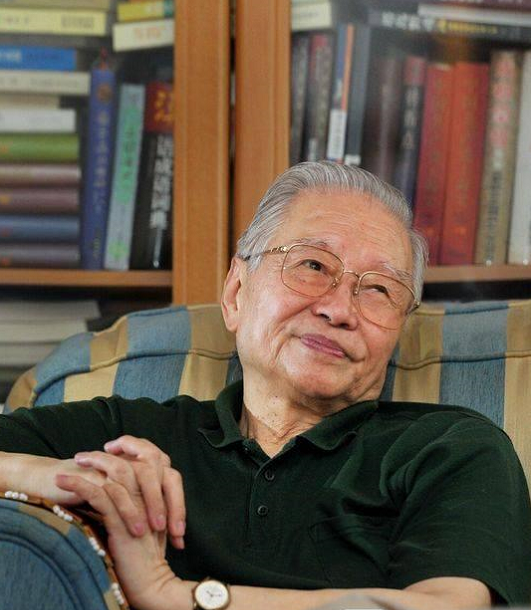

His name is Wang Huo, whose old name is Wang Hongbo. The centenarian is a writer born in Nantong, Jiangsu. Recently, the staff member of the Memorial Hall finally got his contact information after making multiple inquiries. In a phone call with Wang, he recalled his past and encouraged the staff member to make new, greater contributions to spreading history.

Today, we present “What does the Nanjing Massacre Have to do with Me” Episode Five Wang Huo: First Reported the Nanjing Massacre to Uphold Fairness and Justice.

Living through the War

On the morning of September 30, the staff member of the Memorial Hall got through to Wang for the first time. He lives in Sichuan. Wang was overjoyed to receive a call from the Memorial Hall. Recalling his past, the centenarian talked with confidence and quick thinking, “I was one of China’s earliest journalists to report the Nanjing Massacre after the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. I think I can live up to the history by writing it out.” His voice sounded loud and clear, full of pride.

Even if the staff member didn’t meet Wang in person, his image jumped into sight during the talk: with a mane of silver hair, a man talks cheerfully and humorously. Even if he is more than 100 years old, he is still in good health and brims with energy and vitality. Today Wang lives a happy life, but he grew up in war.

“In 1924, I was born in Shanghai. My parents took me to Nanjing at the age of six and we lived there for many years. In 1937, I became a middle school student. After the start of China’s whole-nation resistance against Japanese aggression, my family escaped to Anhui, Hubei, and finally came to Hong Kong,” Wang recalled his experiences during his teenage years.

In 1942, full of passion to resist Japanese aggression, 18-year-old Wang broke through the enemy’s blockade and went to Southwest China alone to pursue education, despite the many hardships along the way. He took trains to Nanjing and then to Hefei. Later, because of the war, he had to climb the mountains and cross the river by boat. Finally, he arrived in Jiangjin, Chongqing via Henan and Shaanxi.

Later, he was admitted to Fudan University as a student majoring in journalism, ranked seventh in the country. At Fudan University, he dreamed of becoming a war correspondent to publish articles about history and brave heroes, just like his mentor Xiao Qian.

Back in the 1940s, Wang published news features on newspapers using names including Wang Huo, Wang Hongbo, and Wang Gongliang. Wang Huo (meaning fire) is a pen name he thought up. He got the inspiration from a quote by famous Russian writer Maxim Gorky, “Use fire to burn down the old world and build a new one.”“The Chinese character Huo is easy to write, fire is red in color, and it can burn down the old world. So I used it in my pen name. I like this pen name.”

Sitting in on a Trial, Reporting the Nanjing Massacre in China for the First Time

In 1946, 22-year-old Wang was still a junior in Fudan University. At that time, he was already a special correspondent and wrote for newspapers including The China Times (then based in Chongqing) and a journal in Shanghai. That February, Wang Yanshi, a professor of journalism at Fudan University, assigned Wang a task: report the trial process of Japanese war criminals in Nanjing as a special correspondent from Shanghai and Nanjing.

The young man was burning with great passion to uphold fairness and justice. The opportunity now came. Filled with hatred against Japanese invaders and his own journalism ideal, Wang went to Nanjing immediately.

“I was shocked as soon as I arrived in Nanjing. It was totally different from the city in my mind. In my memory, the street of Nanjing was busting with activity. But in 1946, I could see few people on the street during the daytime and it looked desolate. The war caused irreparable damage to Nanjing,” Wang recalled.

In Nanjing, the weather is cold and damp in winter. Despite the winter chill, Wang spent days in Nanjing carrying out studies on the Nanjing Massacre, interviewing the survivors of the Nanjing Massacre, and witnessing the discovery of the burial site for victims. He also sat in on the trial of Tani Hisaoat the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal. That day, quite a few victims of the Nanjing Massacre appeared as a witness. “A young woman walked into court in the company of her husband, concealing her face full of scars left by knife wounds with a scarf. She was there to testify to the crimes committed by Japanese troops in Nanjing. She was Li Xiuying,” Wang said.

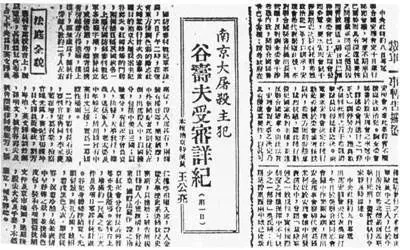

“At that time, not everyone had the courage to stand up. So Li caught my attention as she volunteered to testify in court. After the trial ended, I contacted her for an interview.” Later, Wang published some long articles on Shanghai-based Ta Kung Pao and Chongqing-based The China Times under the pen name of Wang Gongliang. Among them were A Detailed Record of the Trial of Nanjing Massacre Principal Criminal Tani Hisao, and The Insulted and Damaged — A Record of Three Survivors of the Nanjing Massacre.

A newspaper clipping from an article about the Nanjing Massacre written by Wang Huo

The Insulted and Damaged — A Record of Three Survivors of the Nanjing Massacre described the unfortunate experiences of Li Xiuying during the Nanjing Massacre. After being published, the article created a great sensation. The article also helped him achieve his dream of upholding fairness and justice through journalism.

In 1949, Wang earned a full scholarship to Columbia University School of Journalism, but he gave up the opportunity. “The People’s Republic of China was about to be established, so I wanted to stay and witness its founding, and contribute to the building of New China. I didn’t want to miss it.”

On October 1, 1949, the day the People’s Republic of China was founded, Wang was listening to a live broadcast at the office of the arts and education department on the third floor of the Shanghai Federation of Trade Unions building. When the man who experienced war and witnessed suffering of Chinese compatriots heard Mao Zedong proclaim the founding of the People’s Republic of China, his excitement was beyond words.

“Every national memorial day for the victims of the Nanjing Massacre, I would think of the survivors and my experiences of interviewing them in Nanjing. I will never forget this history,” he said.

Portraying the Image of a Woman Who Would Rather Die Than Surrender Based on the Story of a Nanjing Massacre Survivor

Wang is still full of admiration for Li Xiuying when talking about her even after so many years. “She is a great heroine. I was the first journalist to interview her and report her story. When I interviewed her, her face looked like that of the protagonist of Song at Midnight… She would rather die than be humiliated. Some say Nanjing residents didn’t resist, but after interviewing these survivors, I know they are absolutely not cowards.”

The woman who resisted against the Japanese soldiers is Li Xiuying. In this photo, she was being sent to the Drum Tower Hospital for treatment (from The Diaries of John Rabe)

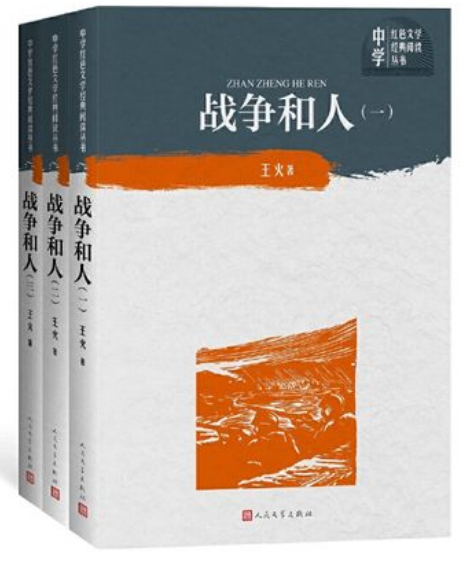

Later, Wang created the War and People trilogy about China’s resistance against Japanese aggression. In his books, he created a female figure who would rather die than submit during the Nanjing Massacre, Mrs. Zhuang, which was based on the experiences of Li Xiuying. “I depicted the terrifying experiences of Mrs. Zhuang in the books largely on the basis of my interview with Li,” Wang said.

Li didn’t forget the interview either. In 1990, when Wang was in Nanjing, “a staff member of the Memorial Hall told me Li always remembered a young reporter once interviewed her and wrote an article. I had planned to visit her, but didn’t do so as I was in a hurry to go to Shanghai to get treatment. This remains a regret for me to this day.”

Li died of illness on December 4, 2004. This will be a regret for the rest of Wang’s life.

Writing Books on the Theme of Wars

On the morning of November 11, the staff member of the Memorial Hall contacted Wang again and his daughter Wang Ling. “My father often talks about conducting interviews in Nanjing after the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. That experience had an influence on his whole life.” Indeed, those extraordinary interviews ignited his interest in recording history and sowed the seeds of creating works on the war of resistance against Japanese aggression in his heart. In the several decades that followed, Wang focused on the theme of wars in his creations.

According to Wang, he wrote The Era Gone Forever, the predecessor of War and People, in his spare time in the early 1960s. Unfortunately, all the manuscripts were destroyed by fire. One day in the 1970s, Wang received a letter from the People’s Literature Publishing House that encouraged him to write the novel again. After careful consideration and given his personal connection with the novel, he decided to create it anew.

However, it was not all pain sailing. In the process of writing, a fatal accident in 1985 almost threw the great work to the winds. To save a little girl out of a deep ditch, Wang hit a steel pipe on the head. As a result, he hurt the retina of his left eye, and suffered an intracranial hemorrhage and a cerebral concussion. After a period of treatment and recuperation, Wang recovered from the intracranial hemorrhage and cerebral concussion, but overwork finally left him blind in the left eye, after retinal detachment caused by a break.

“Although I got blind in one eye, I still wanted to bring the limited light and warmth I could see to more people through words.” With the creative spark ignited, Wang completed the second and third book of War and People, creating typical characters that come to life and depicting heroic and stirring scenes during the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. This epic was won China’s Mao Dun Literature Prizeunanimously in 1997.

“Without real-life experiences, I wouldn’t have completed this work,” Wang said. Indeed, what he saw and heard and his past experiences provided inspiration for his creation. He used words to describe the hard years of revolution he experienced, as well as stories about people and things he saw, heard and experienced. His works eulogize Chinese heroes shining light in the flames of war.

In 1995, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War, the China Writers Association issued a commemorative nameplate to 337 writers, including Wang, to recognize the role they played in the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.

“I love China and the Communist Party of China. China must get strong and prosperous to protect itself against aggression. I have written dozens of books, and I have been working for the fight against aggression.”