“What does the Nanjing Massacre Have to Do with Me” Episode Nine Huang Shunming: Adding a Human Touch to Historical Memory

Ahead of the Tomb-Sweeping Day this year, Huang Shunming, a City University of Hong Kong graduate with a doctoral degree, and a professor of the College of Literature and Journalism and a doctoral supervisor at Sichuan University, came to the Memorial Hall and carried out a “field survey” at the comment area in the Epilogue of the Historical Materials Exhibit Hall. Standing with his backpack, he observed the behavior of the visitors and what messages they left, recording the details on his mobile phone. For 10 days in a row, Huang worked for more than six hours every day, from morning to afternoon. Since 2011, Huang has conducted the survey at the Memorial Hall almost every year, trying to add a human touch to the history of the Nanjing Massacre.

Today we present “What does the Nanjing Massacre Have to do with Me” Episode Nine Huang Shunming: Adding a Human Touch to Historical Memory.

A scholar “keeping an account” in the “field”

“I came to the comment area. Quite a few visitors were waiting to leave a message there. In front of the third comment book, I saw a gray-haired man leaving his message, accompanied by two elderly women, albeit younger than him. After he finished, I talked with him for a while. When I asked him what he wrote, he said he wrote a quote from a great man: ‘Always remember the great achievements of the martyrs. Think about the past in the name of revolution. Forgetting the past means betrayal.’ The old man is already 80 years old. He comes from Xuzhou in Jiangsu...”

Those are some of the words kept in the memo of Huang’s mobile phone. During the 10 days, he wrote tens of thousands of words, calling them his “field notes”!

The “field survey” is part of a National Social Science Fund of China project meant to study how visitors find a memory at the Memorial Hall and what role the Memorial Hall plays in forging that memory.

One time, Huang wrote, “A boy (a sophomore in high school, dressed in a school uniform) from Hefei, Anhui wrote a poem on the fourth machine: ‘The blood of three hundred thousand lives flows like rivers; the corpses pile up like mountains. Never forget the day of national humiliation; make concerted efforts to build our country.’ After he submitted the message, I talked with him for a while. When I asked him how he came up with the message, he replied that he first had some ideas when his teacher told them about the history of the Nanjing massacre in class, but his feelings got deeper after visiting the Memorial Hall in person. He also told me the school organized the visit.”

In another “field note”, Huang wrote about a young woman in a cream-colored coat and with long hair coming down over her shoulders. “She left a message on the third machine: “The past blood and tears must not be forgotten. We should remember history and build on our own strength.” She took a photo of her message with her mobile phone. But then she thought it over and added two exclamation marks and deleted two Chinese characters to make the message sound more powerful. Before submitting the message, she took a photo again.”

Observing how visitors’ memory is formed

Huang set aside two weeks around the Tomb-Sweeping Day for the “field survey” at the Memorial Hall. Why would he observe how the visitors left a message and what they wrote? What’s the point of doing that? “Through historical exhibitions, the Memorial Hall tells the history to visitors in a systematic way, and while leaving a message during a visit to the exhibitions, the visitors will experience some psychological changes. If I don’t know how they expressed themselves, I won’t be able to understand the connection between them and the exhibit during the visit,” Huang said.

During the 10 days, Huang immersed himself in his work, standing or walking around in the comment area. “I must observe and listen carefully all the time so that I won’t miss anything.” In his opinion, only by integrating into the “field” can he find some interesting interactions and remarks.

“Some people may just whisper. But you know what? Even a whisper can be an important detail. Then you’ll see he take a look at the messages left by other visitors and leave his message after getting some inspiration,” he said.

What impressed Huang most was a visitor who spent a long time designing her message. “At first she quoted the well-known words said by Li Xiuying, a Nanjing Massacre survivor who has passed away, ‘Remember the history, not the hatred,’ and then she quoted an old Chinese saying, ‘History, if not forgotten, can serve as a guide for the future’ before adding her own words. That was already a good message. I thought she was going to submit it, but she didn’t. Instead, she clicked the Clear button and wrote some words displayed in the Meditation Hall. I asked her why she deleted the first message, and she said she searched the Internet and found a better one. She told me she is studying at a university in Nanjing and has been thinking about visiting the Memorial Hall for a long time.”

Huang observes visitors of all age groups to understand the influence of age on visitors’ memory. When he sees children, he would ask them whether they wrote the message themselves or their parents taught it to them. “Although they are young, some children are able to express themselves and talk about their thoughts.”

Huang found almost all visitors would talk about memory and their reaction after they visited the historical exhibition. “The most frequently used words are ‘Wuwang Guochi, Zhenai Heping (Never forget national humiliation, cherish peace). ‘Qianshibuwang, Houshizhishi’ (History, if not forgotten, can serve as a guide for the future), an old Chinese saying quoted by Zhou Enlai and displayed on the wall of the Epilogue, is also frequently used.”

In the next stage, Huang will lead his research team to carry out a systematic analysis of visitors’ messages collected during this period. The analysis results will be a significant part of his papers or monographs.

Diving into the history of the Nanjing Massacre for over a decade

Huang frankly said that he puts the focus of his research on the collective memory of the history of the Nanjing Massacre because he believes it is of both academic value and practical significance. His research started in 2011. That year, Li Hongtao, a fellow student who graduated from the City University of Hong Kong with a doctoral degree and now a professor at the College of Media and International Culture, Zhejiang University, successfully applied for a Humanities and Social Sciences Fund project (Remembering to Forget: Constructing and Disseminating the Collective Memory of the Nanjing Massacre) sponsored by the Ministry of Education. At first, they were not clear what research results they could produce, and “we just decided to think and try from different perspectives, and explore new ideas during the process.”

The two scholars first looked at the changes in media narratives about the Nanjing Massacre during the more than 60 years after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. In 2014, they published their first paper about that historical memory, “Humiliating” Narratives and Constructing Cultural Traumas: An Analysis of People’s Daily Articles (from 1949 to 2012) in Memory of the Nanjing Massacre.

The next year, Huang and Li turned their attention to how Chinese and foreign users on Wikipedia wrote articles containing entries related to the Nanjing Massacre. “The users wrote more than 1,600 versions in almost 10 years. We studied how these items constructed the memories about the Nanjing Massacre,” Huang said.

They also paid attention to the reports on memorial events published by several media groups in Nanjing on the first national memorial day for the victims of the Nanjing Massacre. Around 2016, Huang started his “field survey” at the Memorial Hall to understand the meaning of the “300000” sign that means three hundred thousand victims in different scenarios at the Memorial Hall.

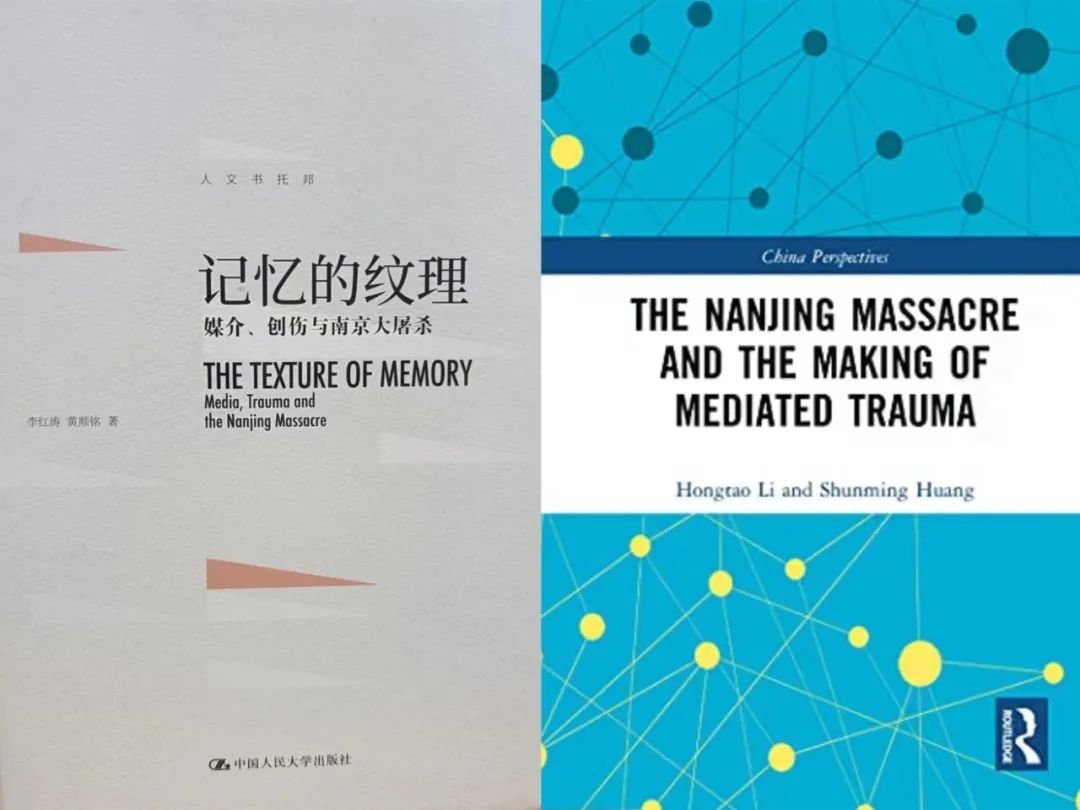

The two scholars included those research results into their book, The Texture of Memory. “The book is the fruit of our work for the past years. During the national memorial day for the victims of the Nanjing Massacre every year, some platforms will publish excerpts from the book. This makes us truly feel the positive role of our academic research,” Huang said. He also said the English edition of the book was published last year by Routledge (headquartered in London, the UK), and work is underway to translate the book into Spanish, funded by the Chinese Academic Translation Project.

The Chinese and English editions of The Texture of Memory

“For a memory that shall never be forgotten”

To carry out research on the collective memory of the history of the Nanjing Massacre, Huang has travelled from Chengdu in Sichuan to Nanjing in Jiangsu for countless times over the past more than 10 years.

Every time he visited the Memorial Hall, he never contacted the Memorial Hall in advance. He just walked into the “field” as a visitor and observed other visitors and the Memorial Hall itself in this way. “One year after The Texture of Memory was published, I got a grant from the National Social Science Fund of China to conduct a project focused on the collective memory of the Nanjing Massacre based on the Memorial Hall. The grant provides financial support for my continued research,” he said.

Huang still remembers his experience of conducting a “field survey” at the Memorial Hall in summer 2016. “In Nanjing, the weather in summer is very hot. At that time, the Memorial Hall didn’t have the reservation policy, so every time I came, a lot of visitors waited in a long line at the Public Memorial Square. In my view, the Memorial Hall is a place of collective memory, and doing the ‘field survey’ in a down-to-earth way there is very necessary.” Although it’s a painstaking process, Huang believes it’s a very crucial job worth keeping at.

During the Qingming Festival in 2019, the Memorial Hall invited Huang to speak at the Zijin Cao Lecture. The title of his speech is Flower as Media: Transnational Movement of Zijin Cao and Nanjing Massacre Memory Construction.

Not long ago, Huang published a translation of a work by famous American communication scholar Barbie Zelizer, Remembering to Forget: Holocaust Memory through the Camera’s Eye. The book reveals the significance of the photographs taken at the liberation of the concentration camps in Germany toward the end of World War II. The book shows how the photographs have become the basis of our memory of the Holocaust and how they have affected our presentations and perceptions of contemporary history’s subsequent atrocities. Huang said the writer is looking at the collective memory of the Holocaust occurring on the western battlefield during World War II from an academic standpoint. “As a Chinese, I will bring research results related to the collective memory of the Holocaust occurring on the eastern and western battlefields during World War II to my class and share them with my students,” he said.

Over these years, Huang has been remembering the history in his own way. On the national memorial day for the victims of the Nanjing Massacre, he always wears a purple scarf. He also plants Zijin Cao in the balcony of his home. “When it flowers, the plant will remind me of my personal connection with the Memorial Hall, which gave me the seed.”

Huang said the memory of the Nanjing Massacre, which is a national trauma, should be passed down from generation to generation. “Communication scholars should be ready to assume the responsibility to let more people around the world know the history through their academic research, by writing books and giving lectures.”