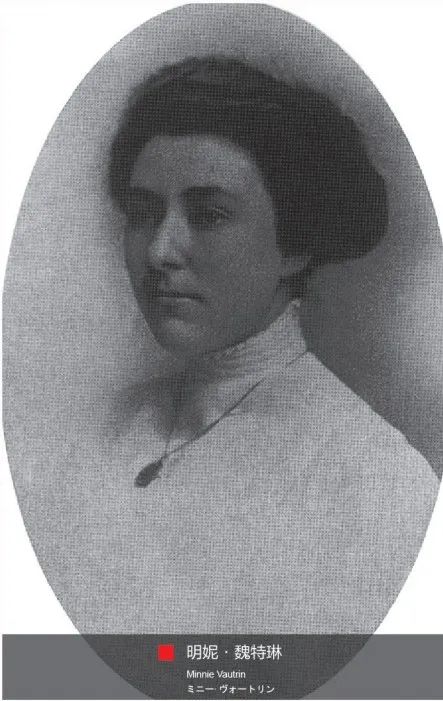

They were in Nanjing (2) | Vautrin: She never gave birth in her life, but had a group of children...

She was Minnie Vautrin (Chinese name Hua Qun). She came to China from the United States in 1912 to teach at Ginling Women's Arts and Science College (now Nanjing Normal University). During the Nanjing Massacre, she stretched her arms to shield the women and children behind her many times, protecting refugees like an old hen protecting chicks. Today is Mother’s Day and Minnie Vautrin’s death anniversary. She had never given birth in her life. “If I had two lives,” she said before she died, “I would still be willing to serve the Chinese.” Today, let us cherish the memory of this great woman.

Remain in Nanjing in times of crisis

The Japanese War of Aggression against China erupted into a full-blown war on July 7, 1937, and Minnie Vautrin was on vacation in Qingdao, Shandong, China. She immediately returned to Nanjing and remained there during the air bombing of Nanjing.

She believed she should remain on campus to take on the responsibility and mission and protect her “children.”

“At 9:00 p.m., a messenger from the U.S. Embassy sent a letter, asking all men and women to evacuate... I feel that after spending eighteen years at Ginling Women's Arts and Science College, and having fourteen years’ contact with neighbors, I have to take on some responsibilities, and this is also my mission, just like men should not abandon ships and women should not abandon their children in distress.

- The Diaries of Minnie Vautrin, August 27, 1937

“After a brief discussion with Catherine, we told the embassy that we would stick with our colleagues and that we thought we would make a big difference at such times. We have also made it clear that we stay behind on our own, and that whatever happens, we make sure that the government or the college will not feel in any way that they are responsible for this.”

- The Diaries of Minnie Vautrin, September 20, 1937

Upon returning to the campus, Minnie Vautrin set about making the campus a refugee shelter for women and children. Before the fall of Nanjing, Ginling Women's Arts and Science College began to accept refugees, and a wealth of women and children flocked into the campus. “We would provide humanitarian services to these women and children who come to our college even if we will have damaged and stained walls. In no way will we close the door to them,” recalled Minnie Vautrin.

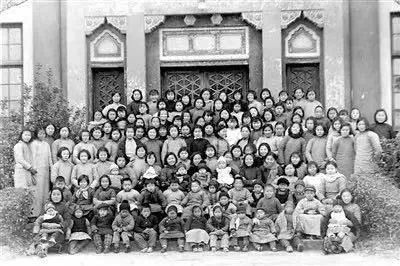

A group photo of Ms. Minnie Vautrin (front row, fourth from left) and some staff members of Ginling Women's Arts and Science College’s refugee shelter

Came forward to protect women and children

On December 13, the Japanese soldiers invaded the city and caused the extremely brutal Nanjing Massacre, which shocked China and abroad. In the terror-stricken period, a large number of women and children flocked to Ginling Women's Arts and Science College. Minnie Vautrin stepped forward and used her tall body to protect Chinese women against the Japanese invaders on campus, erecting a huge Noah’s Ark for tens of thousands of women and children in Nanjing.

Women and children taking refuge at Ginling Women's Arts and Science College

After invading the city, Japanese soldiers would every day go to Ginling Women's Arts and Science College to arrest people, raping women and robbing and looting. They not only forced their entry through the school’s main entrance and side doors, but also climbed over the fence, and even crawled through the low fence at night to search for and rape women.

Minnie Vautrin patrolled the campus all day long and arranged for foreign men to take turns keeping watch at night to prevent Japanese soldiers from tracking down women. Many Japanese soldiers were furious, threatening her with bloodstained bayonets. Others slapped Minnie Vautrin across the face hard. She sometimes had to watch helplessly innocent women being taken away, raped, killed...

“I saw two Japanese soldiers pushing the door of the central building, demanding that the door be opened. I said there was no key. A Japanese soldier said, “There are Chinese soldiers and they are the enemies of Japan.” I said, “No soldiers.” Mr. Li, who was with me, echoed. They slapped me in the face, and also hit Mr. Li hard, insisting that the door be opened... I’ll never forget the scene of people kneeling by the roadside, Mary, Mrs. Cheng and I standing, with rustling dead leaves, a whining wind and the miserable cries of women who were being taken away.”

- The Diaries of Minnie Vautrin, December 17, 1937

“At dawn, women, young girls, and children, who looked frightened, came flooding in. We could only let them in, but there was no accommodation for them. We told them they could only sleep on the open grass... These days, I ran all over the campus, saying aloud “This is an American school!” Oftentimes, the Japanese would leave, but sometimes they ignored what I said and stared at me ferociously, sometimes waving bayonets at me.”

- The Diaries of Minnie Vautrin, December 18, 1937

“ I spent the rest of the morning running from one side of the campus to the other, driving Japanese soldiers away. I went to Nanshan three times, back to the rear of the campus, and then went to the faculty building. It was said that two Japanese soldiers had gone upstairs. In room No. 538, I saw a guy standing on the door and another raping a girl. Seeing my appearance and the letter from the Japanese embassy in my hand, they ran away in a hurry. Deep down, I wish I had the strength to thump them.”

- The Diaries of Minnie Vautrin, December 19, 1937

An atmosphere of pain hung heavy in the refugee camps, because many refugees had lost their beloved ones. Minnie Vautrin comforted and encouraged them, and often invited neighbors and children to parties, giving them the confidence of victory and the courage to live.

“In the South Painting Studio, around one hundred and seventy women selected from the Central Building attended the sermon meeting. Miss Wang taught them to sing, and Mr. Paul Tang performed a sermon... At the same time, we also held a sermon for about 150 children aged from nine to fourteen in the Science Building. They were pleased when they learned to sing the first sentence “This is God’s world.” They were attracted by the story told by Miss Xue. These sermons were held at a good time because everyone was eager for comfort.”

- The Diaries of Minnie Vautrin, January 19, 1938

“Over five hundred women gathered in the auditorium to pray on Good Friday... The four blind girl refugees sang a special song. It was like a miracle that they could bring the breath of life to so many people in these sad and agonizing days.”

- The Diaries of Minnie Vautrin, April 15, 1938

Great motherhood is remembered forever

Working in a terrifying and stressful environment for a long time took a great toll on Minnie Vautrin: Minnie Vautrin suffered a nervous breakdown in the spring of 1940. Soon afterwards, Minnie Vautrin left Nanjing for the United States for treatment. On May 14, 1941, she departed from this world.

Minnie Vautrin never gave birth in her life, but she devoted her life to the Chinese people.

Standing in the historical material exhibition hall of the Memorial Hall is a bronze statue of Minnie Vautrin, showing her as stretching her arms to protect the terrified Chinese women and children behind her. Engraved above the bronze statue is a quote from the German friend John Rabe, chairman of the International Committee of the Nanjing Safety Zone at the time: “Minnie Vautrin protects them (refugees) like an old brooding hen protecting chicks!”

On July 20, 2002, Cindy Vautrin, niece of Minnie Vautrin, and her daughter came to Nanjing to donate The Diaries of Minnie Vautrin and over 100 pieces of precious cultural relics to the Memorial Hall. Minnie Vautrin’s relics were kept by Cindy because she was never married for life, and Cindy was her eldest niece.

According to Cindy, she believed that Minnie Vautrin’s relics would create the best value to be put at the Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders. Those evidence materials would also be provided to the Memorial Hall for reproduction free of charge.

Cindy Vautrin (first from left)

A few days ago, the editor sent a greeting email to Cindy Vautrin, who was in the United States.

Cindy said that she learned about the crimes perpetrated by the Japanese invaders during the Nanjing Massacre and the situation of the Japanese army occupying Nanjing after 1937 through Minnie Vautrin’s letters to her relatives and friends during the Nanjing Massacre period. After her trip to Nanjing in 2002, she learned about the real history, and also understood her great-aunt’s good deeds to protect Chinese refugees, as well as why her great-aunt regarded China as her home, and the Chinese people’s affections for her great-aunt.

Amidst the wooded area of Nanjing Normal University is a bronze statue of Minnie Vautrin. Cindy came here in 2002 and stood for a long time in front of the bronze statue. “It would be great to plant chrysanthemums in front of the bronze statue, as it was my great-aunt’s favorite flower,” said Cindy.

On the campus of Nanjing Normal University, a bronze statue of Ms. Minnie Vautrin stands among the lush trees, smiling at passers-by. The stele at the bottom of the bronze statue is inscribed with four Chinese characters meaning Eternal Life for Ginling.

Thank you for everything you did. We have always borne these in mind.